Black Hat USA 2024: From Doxing to Doorstep - Exposing Privacy Intrusion Techniques used by Hackers for Extortion

At Black Hat USA 2024 in Las Vegas, I presented “From Doxing to Doorstep: Exposing Privacy Intrusion Techniques used by Hackers for Extortion.”

This blog post provides a detailed breakdown of the research that I presented.

Click to view presentation abstract

Doxing, initially a practice for undermining hackers’ online anonymity by “dropping docs”, has evolved into a tool used for real-world extortion, employing violence-as-a-service tactics like “brickings”, “firebombings” and “shootings”. This escalation reflects a troubling trend where digital conflicts manifest physically and is facilitated by legal gray areas. The ambiguous stance on doxing in U.S. policy complicates accountability, making it a pressing concern for privacy and personal safety.

This talk features first-hand insights from individuals engaged in doxing, through exclusive interviews, which have never been disclosed to the public previously. This includes a wanted threat actor involved in a DEA Data Portal hack, and an administrator of the largest doxing website, Doxbin. This provides a rare glimpse into the secretive world of doxing, and lesser-known privacy intrusion techniques, such as impersonating law enforcement and submitting fraudulent Emergency Data Requests.

The session concludes with actionable advice on safeguarding personal privacy to reduce the risk and impact of doxing. Attendees will leave equipped with knowledge of preventative measures, alongside a call for policy reform to address gaps in U.S. legal frameworks that enable doxing to thrive. This talk not only sheds light on the dark underbelly of cyber extortion, but also fosters a dialogue on essential changes needed to curb the proliferation of doxing.

1. Introduction

This research has been informed by interviews I personally conducted with hackers involved in doxing for extortion.

This included a wanted threat actor who participated in breaching a US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) Data Portal, and a Doxbin administrator. At the end of the talk, I shared a link to view the transcript of these interviews, marking their first public release.

This blog post will also provide actionable advice on safeguarding your privacy and personal safety, as well as an understanding of the gaps in legal frameworks that enables doxing to thrive.

My name is Jacob Larsen, and I work as an offensive security team lead at CyberCX where I secure our customer’s applications and infrastructure through security testing. However, in the evenings I work as a threat researcher, and I have been tracking a lot of different underground cyber crime groups since 2016.

The research I am sharing today is what I have completed in a personal capacity, as I have a personal connection to doxing.

9 years ago, I was the victim of doxing. I had my personal information released on a doxing website. My privacy was violated, my safety was threatened, and I was demanded to pay an extortion. This was because I had an online gaming account with a rare username which they wanted. I didn’t meet their demands, and I lived in fear of what might happen to me. Ever since then, I have followed the weird online subculture surrounding doxing and those who participate in it.

2. ViLE and Doxbin

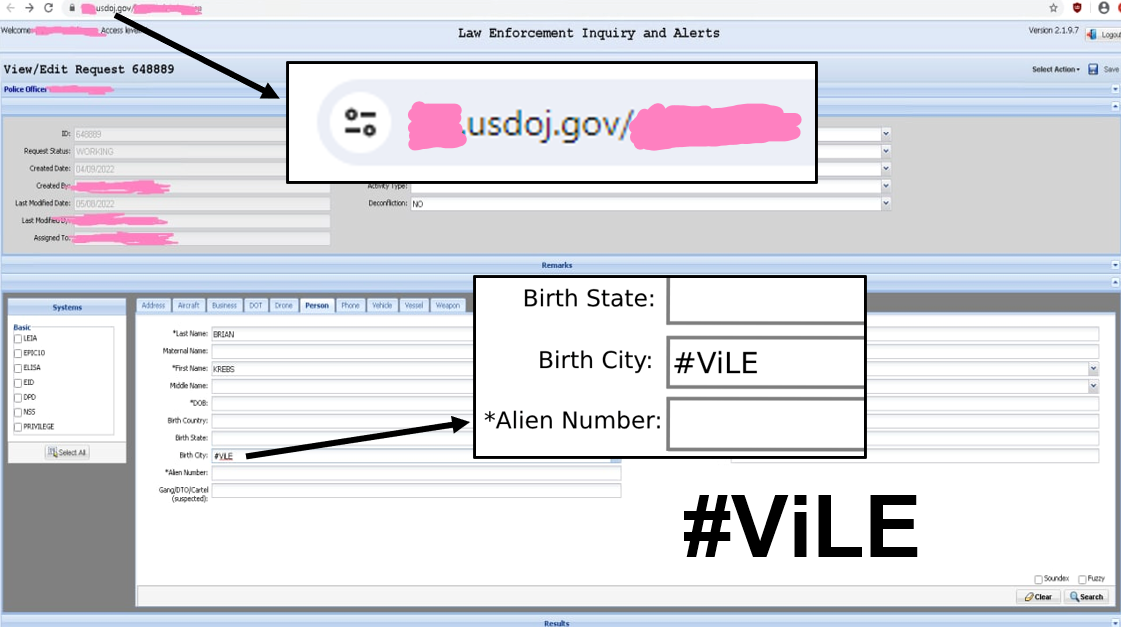

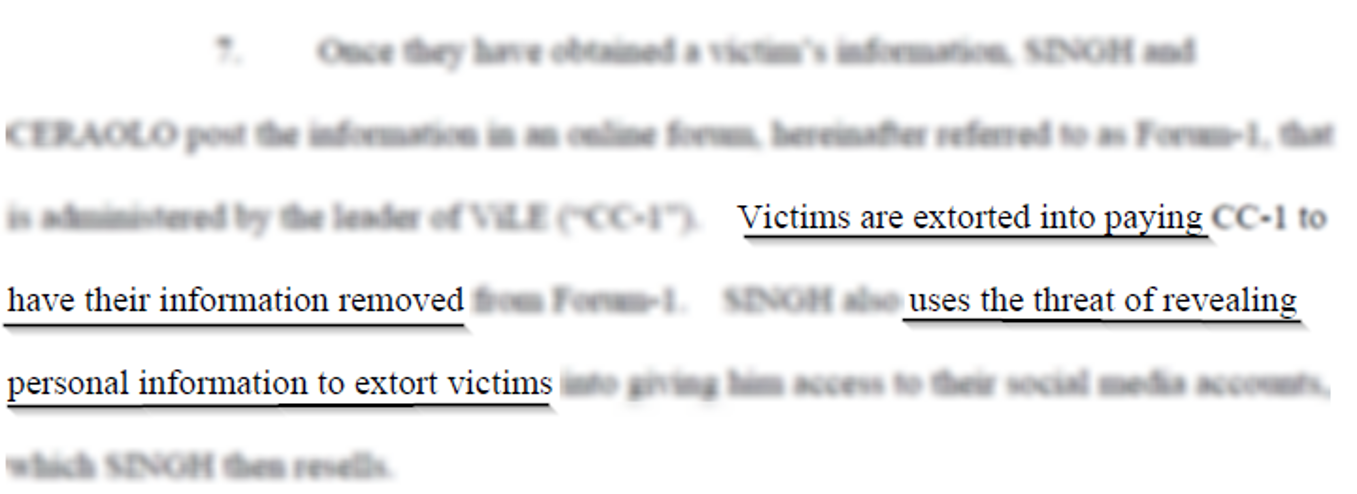

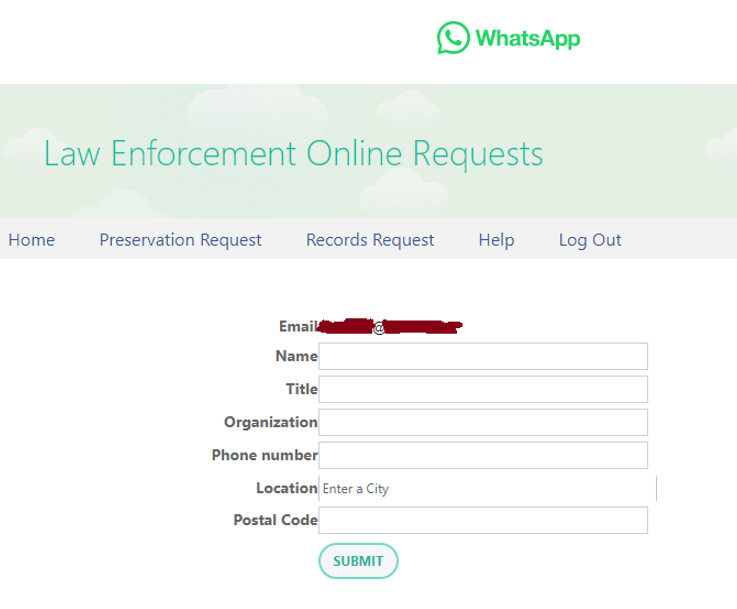

This story behind this research began in March 2023, when two members of the notorious doxing called ‘ViLE’ were charged by the Department of Homeland Security for compromising the DEA web portal shown in the image below. This portal allowed them to search for anyone’s personal information across 16 different US federal law enforcement databases. This included finding information such as full names, residential addresses, emails, mobile numbers, owned property, vehicles, licenses and much more.

The affidavit included that the ViLE members used the compromised access to threaten victims with release of their personal information, unless extortion demands were met. They used this access for doxing, which is slang for “dropping documents”, or dropping information that publicly links someone’s real identity with their online username. The intention of doxing is to intimidate victims by making them fearful of what might happen to them, when their personal information is released on a website where it won’t be taken down. This creates a lot of concern for victims of doxing, as the typical advice provided, that it will “just go away with time”, just doesn’t apply.

This is why adversaries choose to post victims doxes on platforms like Doxbin. Doxbin is a doxing website that prides themselves on being able to offer adversaries a location where they can upload victim’s doxes without them being taken down. As per their website it says:

If your info goes up, it’s not coming down unless it’s inaccurate or it breaks our terms of service.

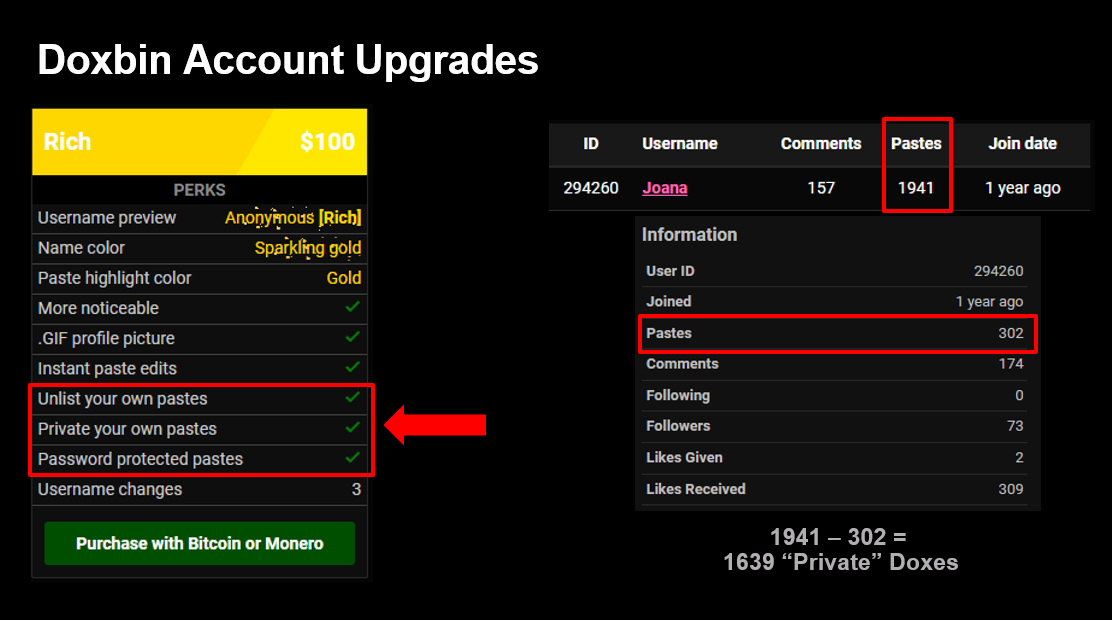

One of the primary features that Doxbin offers to upgraded users, is the ability to publish private doxes. This means an adversary can upload a victims dox and then send them a private link to it on Doxbin. Next, the adversary will attempt to extort the victim by threatening to release their personal information publicly and to the Doxbin community. Due to this simple functionality, Doxbin has become the largest doxing community online and has amassed over 300,000 users and 165,000 published doxes.

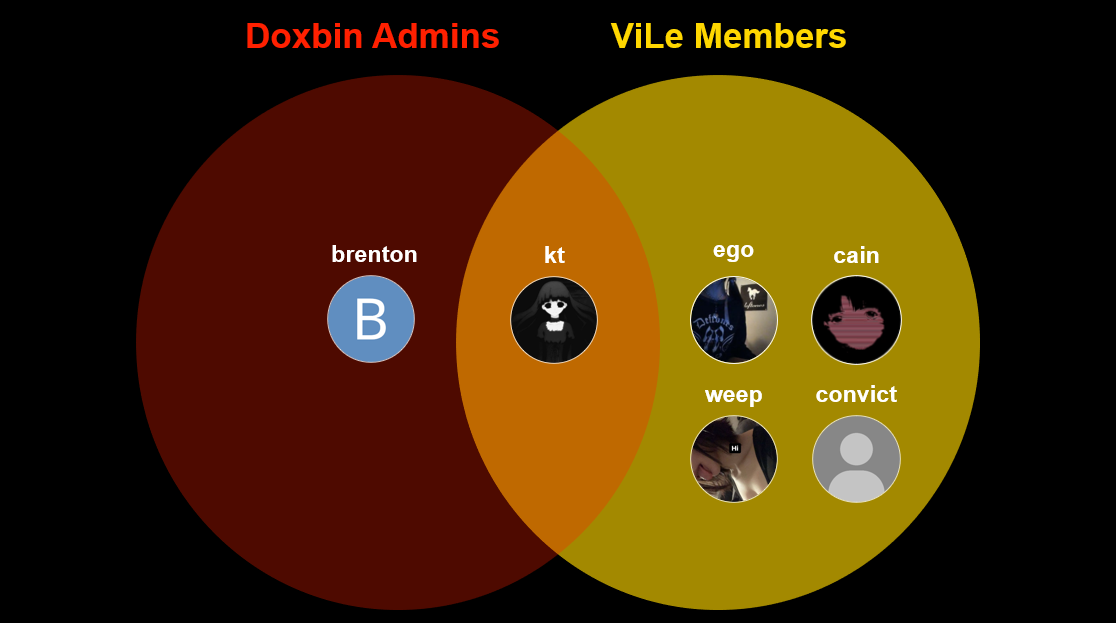

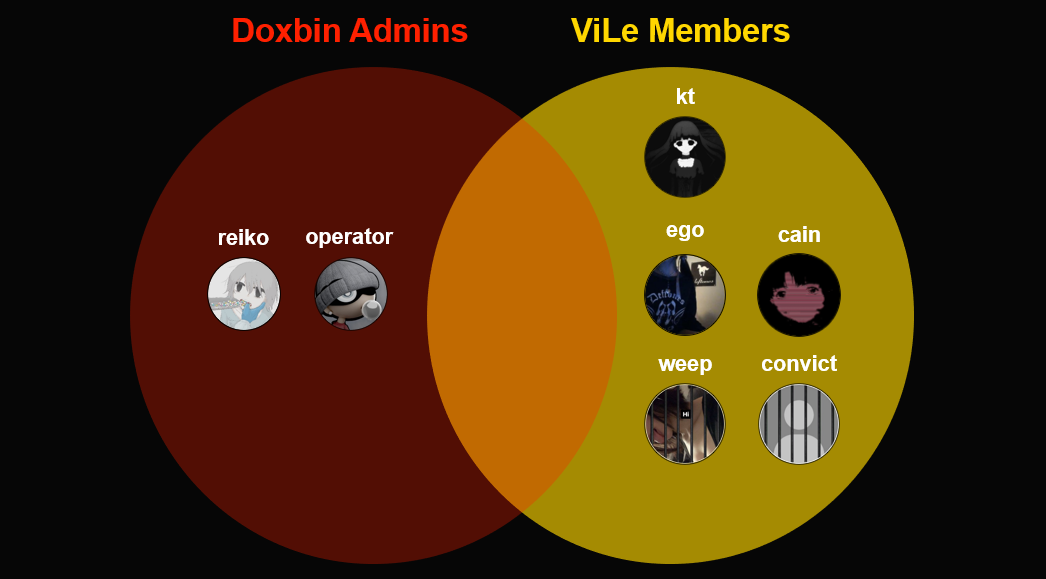

Doxbin was founded in 2018 by two actors called “Kt” and “Brenton”. “Kt” is also one of the 5 members of the doxing gang ViLE which breached the DEA data portal. The other members are “Ego”, “Cain”, “Weep”, and “Convict”. “Weep” and “Convict” were the two members that were charged by authorities in March 2023, and who pled guilty in June 2024. The remaining members “Kt”, “Ego” and “Cain” are wanted for their involvement, as per the Department of Homeland Security’s latest commentary in June 2024.

HSI New York’s El Dorado Task Force will continue to work with law enforcement partners to uncover evidence until every member of the ViLE group and similar criminal organizations are brought to justice.

3. ‘Ego’ and Emergency Data Requests

To get better insights into doxing techniques used, I personally conducted an interview with “Ego”, one of the members of ViLE that wasn’t apprehended. The transcript of the interview is available here.

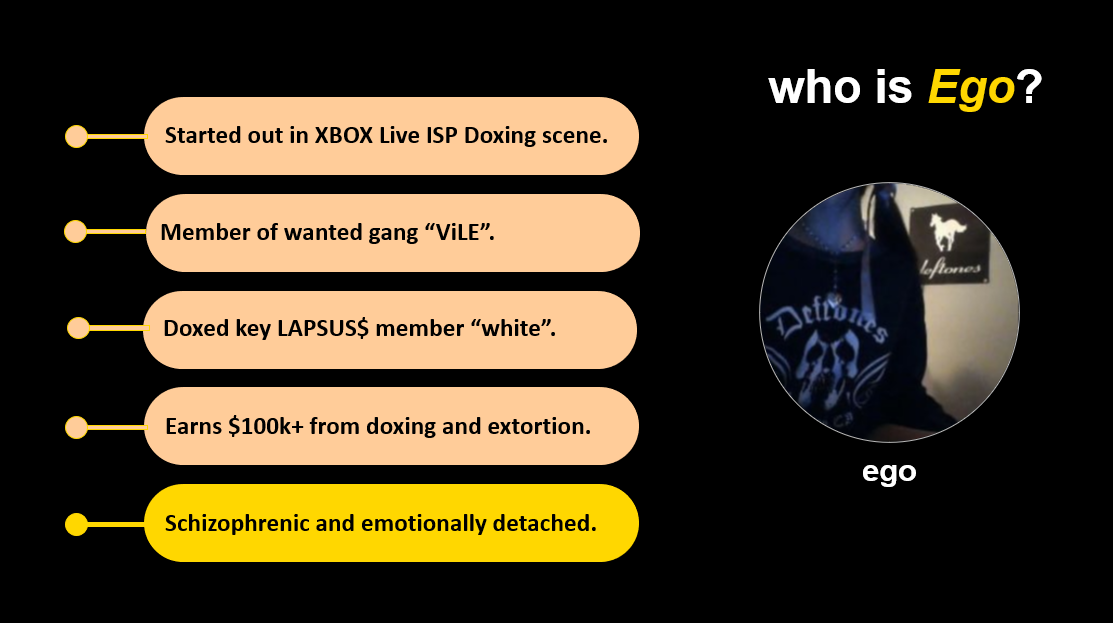

Ego first started out in the Xbox Live Internet Service Provider (ISP) doxing scene when he was much younger. This is where he found the IP address of other players and used this to hit them using a denial of service attack. This was done so he could target them and extort them for money.

He later joined Doxbin and became a member of ViLE as his skillset had evolved. He was ranked on Doxbin as “Clique” which means he is friends of the owner. He even contributed to the unmasking of a key LAPSUS$ member called “white” in 2022 leading to their arrest.

Now he is an experienced social engineer and hacker who boasts earning a significant income from doxing and extortion activities. In the interview, he also shared that he lives with schizophrenia, and acknowledged that it makes him emotionally detached, so he doesn’t have much remorse or empathy for his victims.

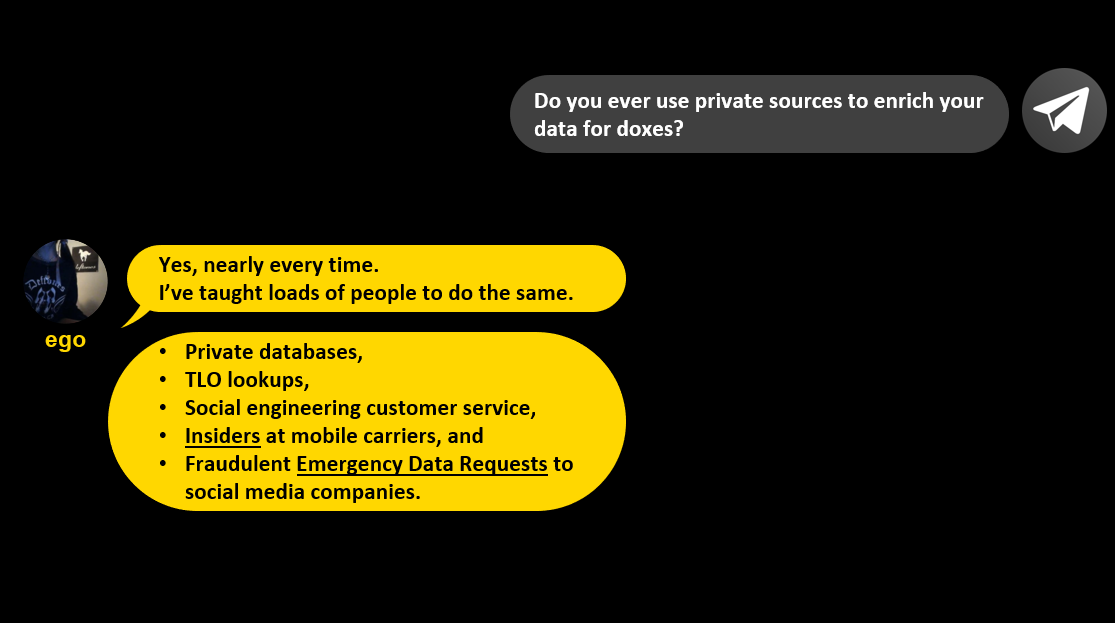

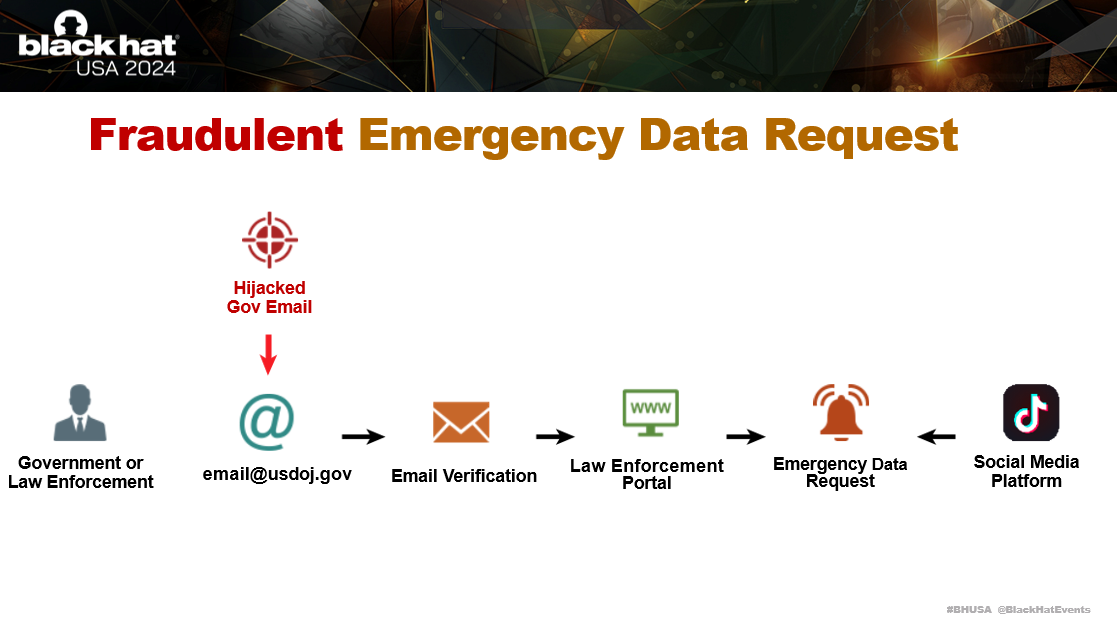

ViLE compromised the DEA data portal by impersonating police officers and using compromised law enforcement passwords. In the interview with Ego, he admitted to using a technique known as fraudulent Emergency Data Requests, “nearly every time”, and that he “taught loads of people to do the same.”

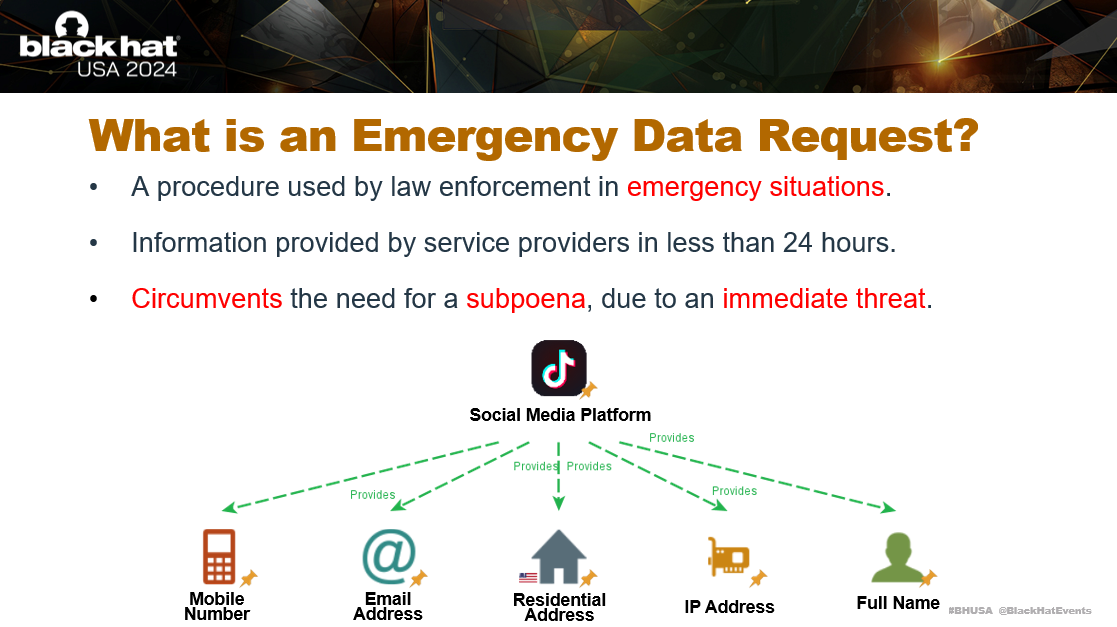

So what is an Emergency Data Request?

An Emergency Data Request is a procedure used by law enforcement agencies for obtaining information on service providers in emergency situations where there is not enough time to get a subpoena. These types of emergency situation could include an immediate threat to public safety or someone’s life.

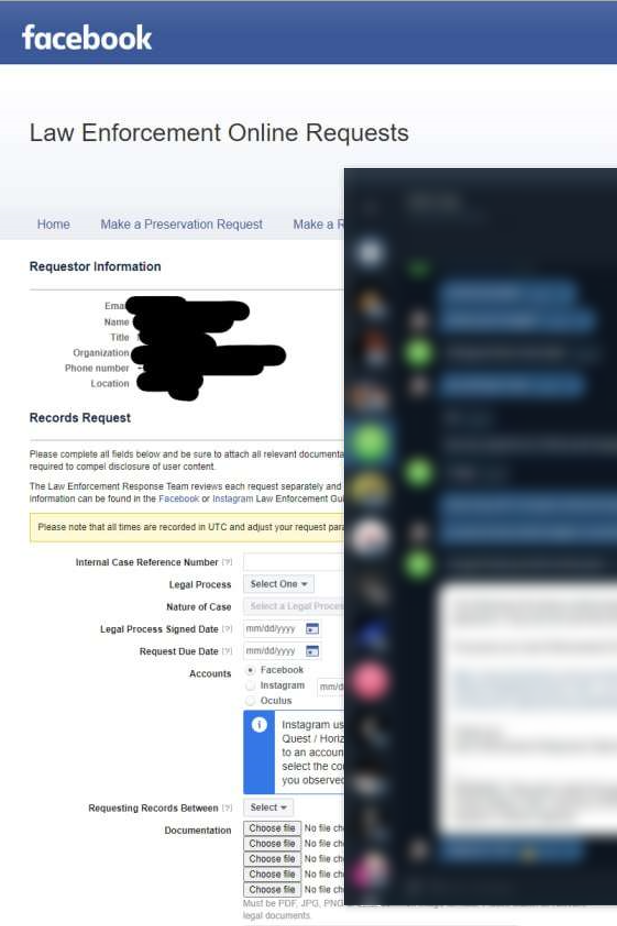

Social media companies like Meta, TikTok and WhatsApp offer “Law Enforcement Panels” to government workers where they can submit an Emergency Data Request and receive information on targeted users within 24 hours. The request simply needs to include a single data point, such as an email or username.

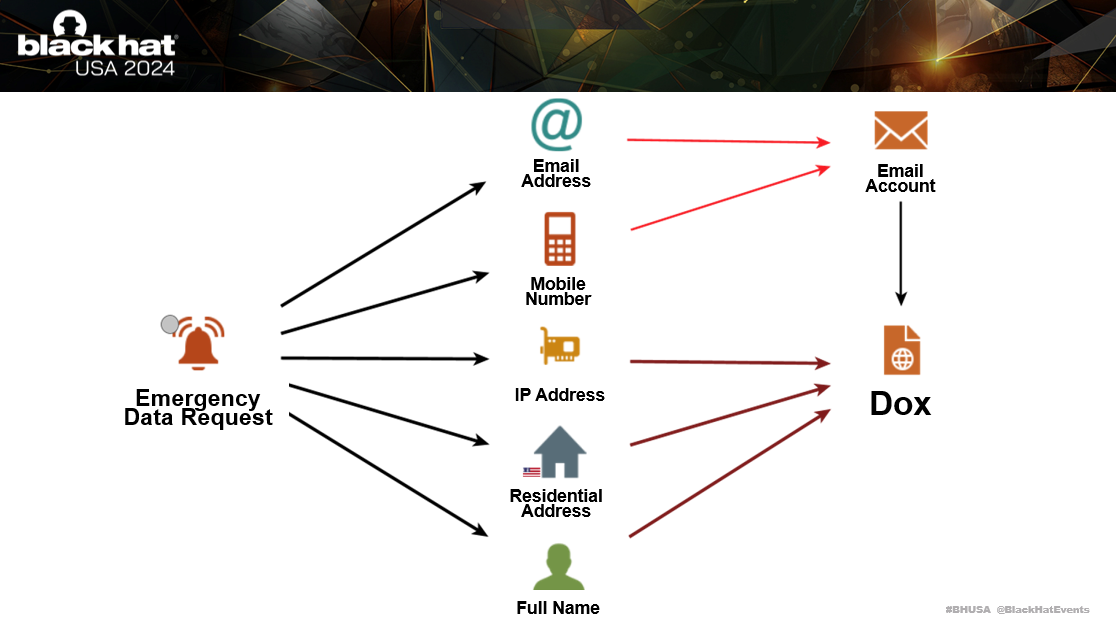

When the request is completed, the information provided includes full name, email, residential address, payment card details, message history, mobile numbers and IP addresses.

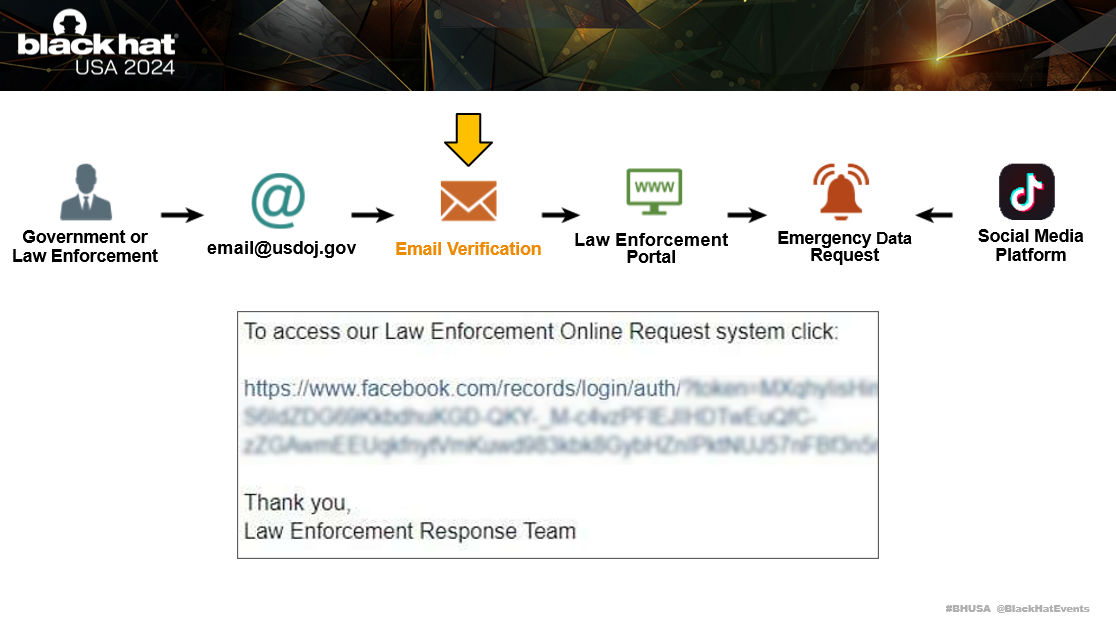

Before an Emergency Data Request can be submitted, an identity verification process is required. For most Law Enforcement Panels, this simply requires a government email address which can receive an authorisation code or link.

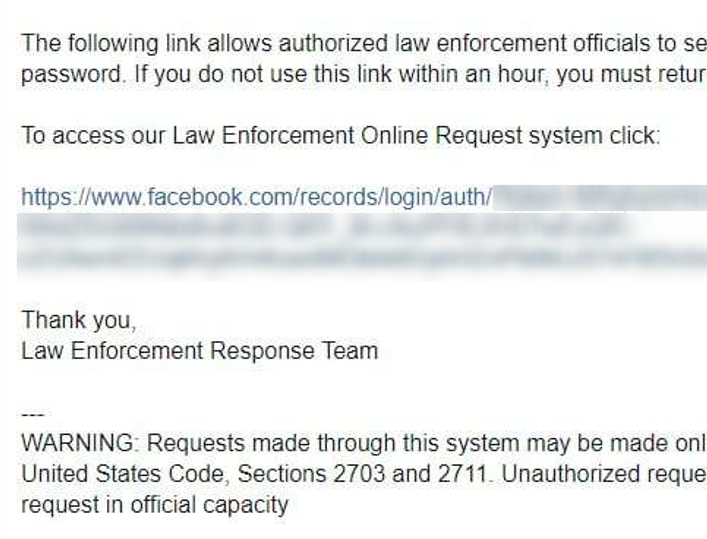

In the slide below you can see an example of the authorisation link sent by email to access the Facebook Law Enforcement Panel.

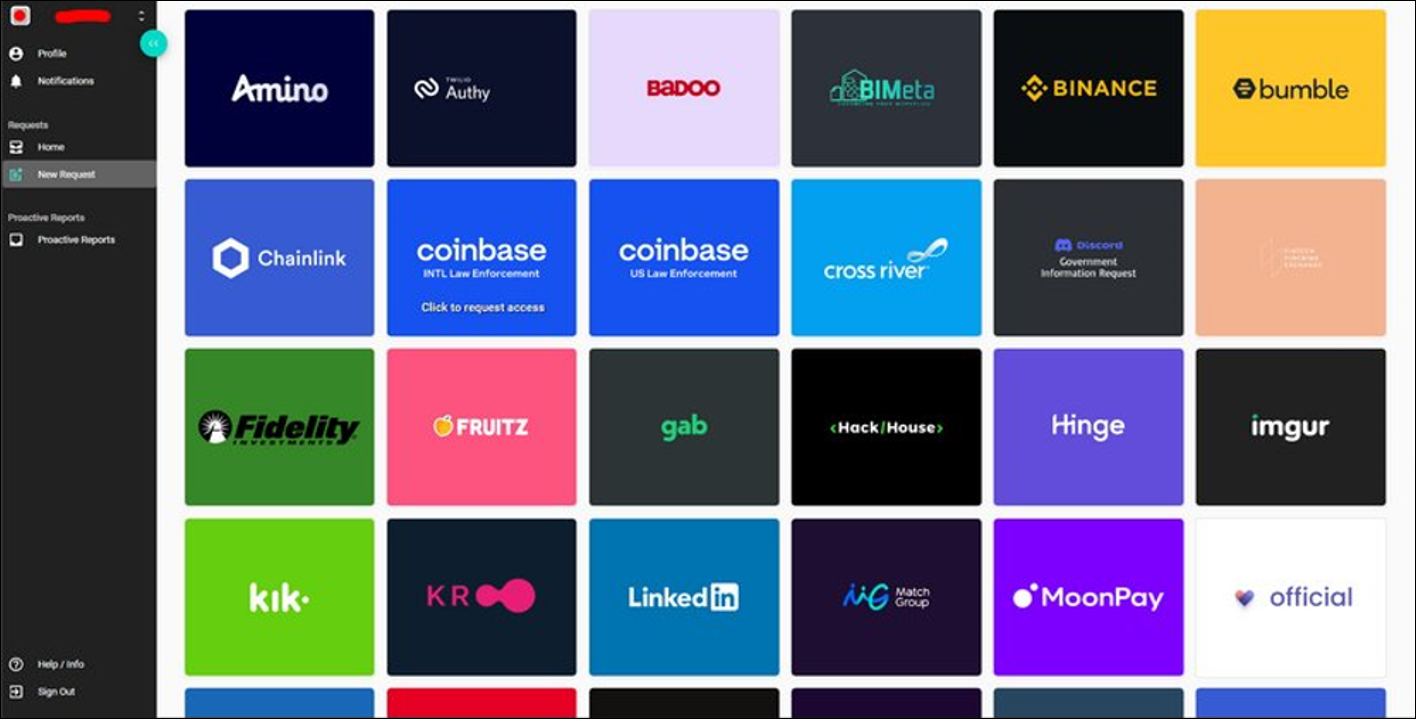

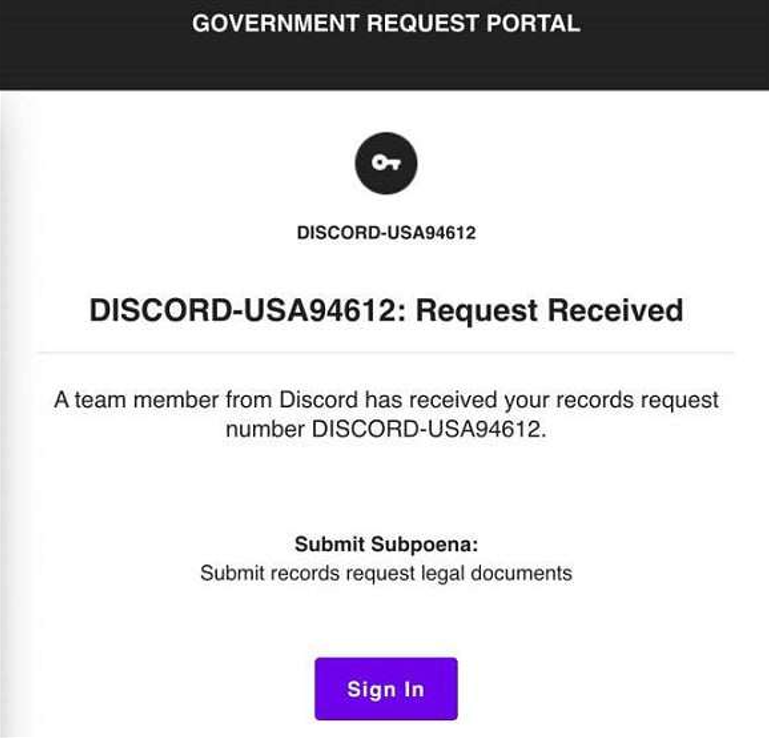

There are also aggregator platforms that exist, which offer government workers a single portal where they can lodge requests. These aggregators will submit the request to multiple service providers at the same time as well as handle the verification process.

The slide below shows a screenshot of one of the platforms where requests can be submitted. You can see examples of different service providers where a request can be sent, such as Discord, Coinbase, LinkedIn and others.

Given the depth of information these service providers have on users, if a fraudulent Emergency Data Request could be completed, it would be the fastest way for an adversary to obtain highly accurate and sensitive data on a victim.

4. Submitting Fraudulent Emergency Data Requests

Submitting a fraudulent request, only requires access to a compromised Government email address. This allows the adversary to use this email address to verify themselves on different law enforcement panels and aggregators. Sometimes there are additional steps, however creating supporting fraudulent documentation is also easily completed.

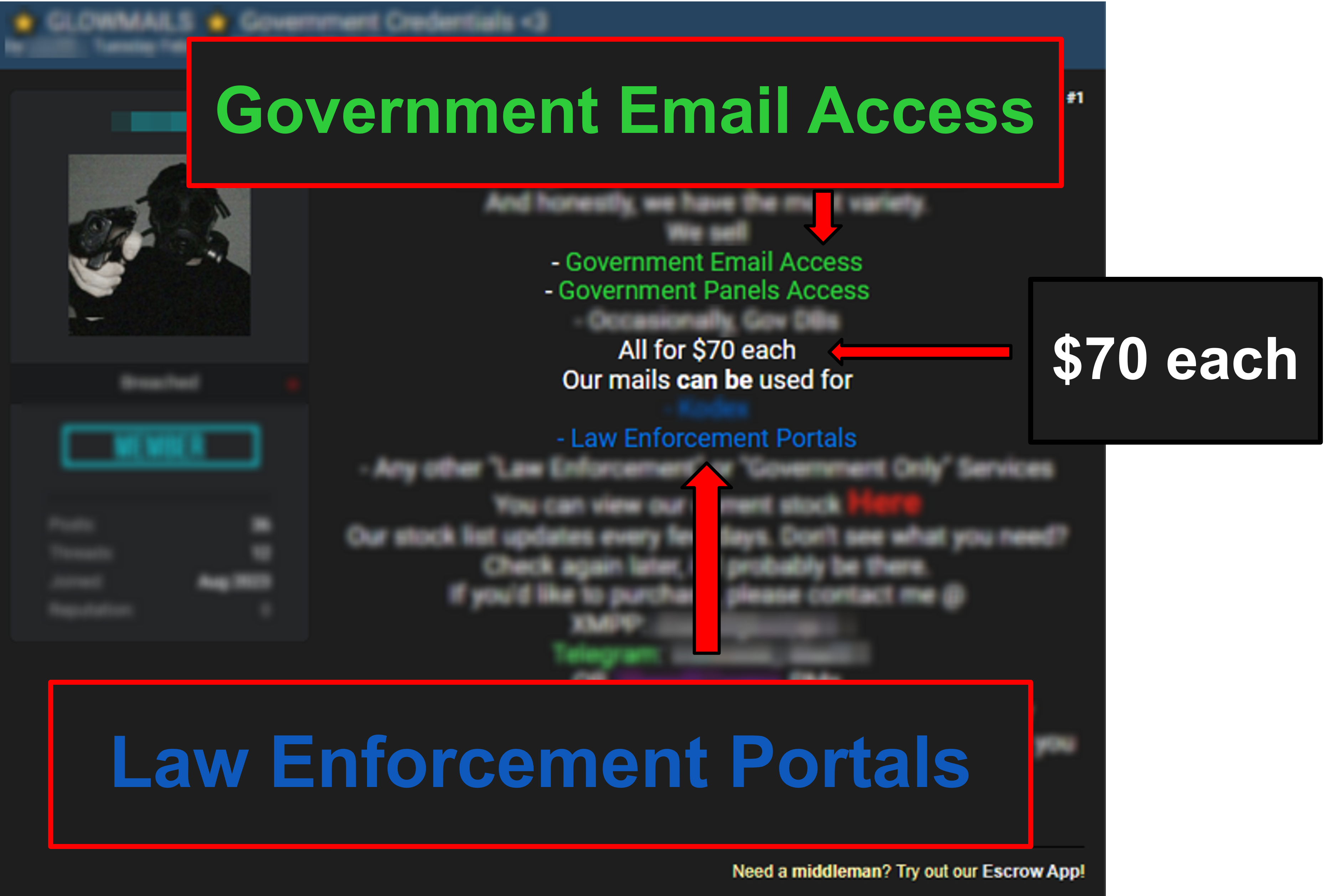

Government Emails can be purchased from a brokers in underground forums and Telegram communities. They have been obtained them from information stealer malware logs, web shells on hijacked Government cPanels, and from phishing.

You can see on the slide below it costs only $70 USD to purchase a government email address which can be used to access a law enforcement panel.

By going undercover as a customer, I was able to infiltrate invite-only Telegram communities where threat actors sell government emails and provide the service to submit fraudulent Emergency Data Requests.

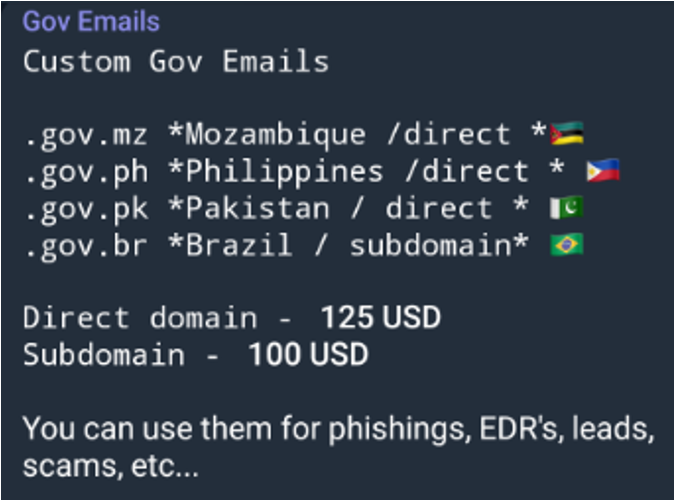

I observed a threat actor selling custom government emails, where adversaries could supply any name they wanted for a government email address to be created from Mozambique, Philippines, Pakistan or Brazil. The cost of this was only $100 USD, and could be used for Emergency Data Requests, as per the image below.

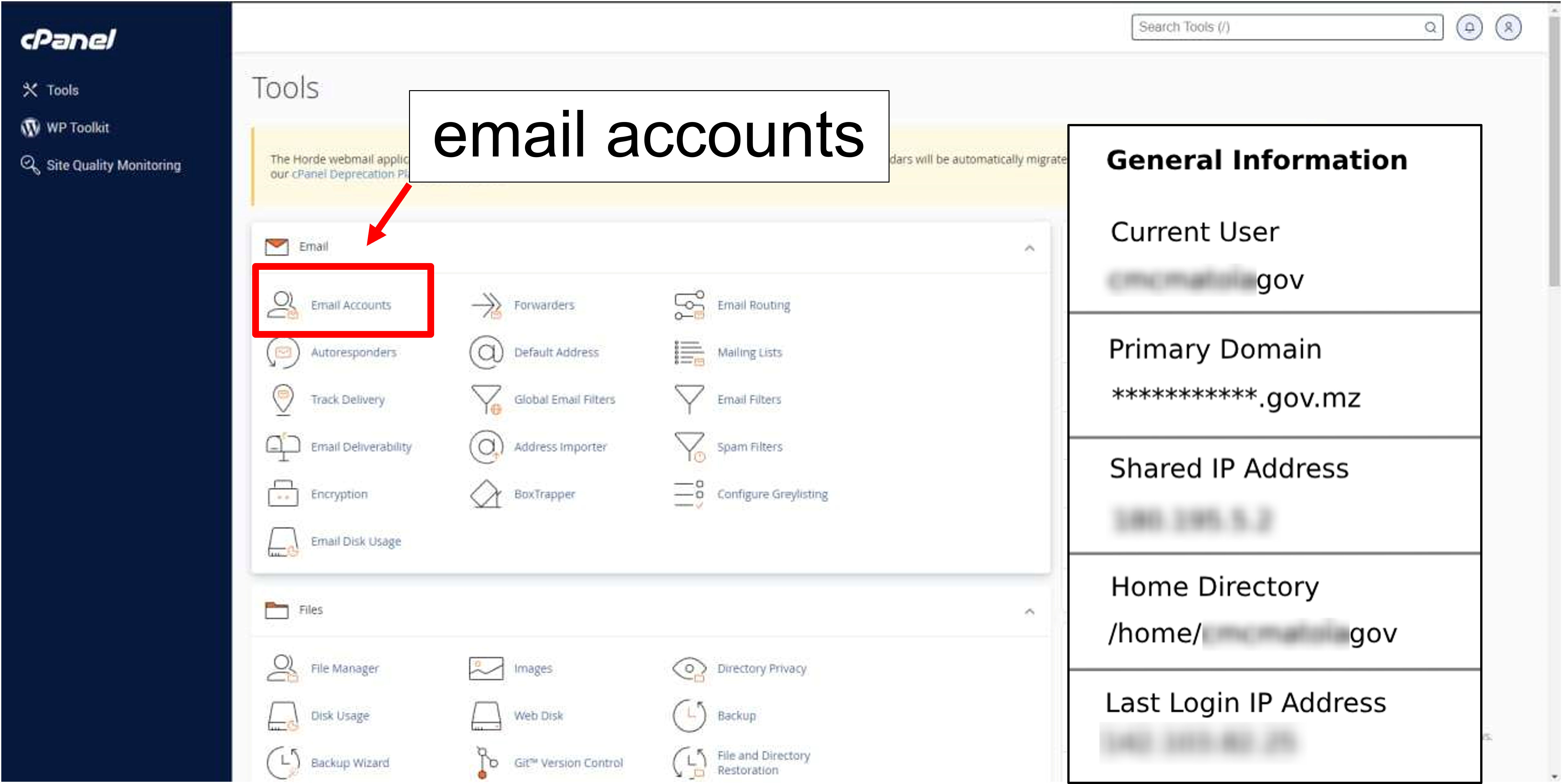

This access was obtained through a hijacked cPanel, and the threat actor was not so careful to leak a screenshot including the public IP address and full domain associated with the cPanel, as seen in the image below.

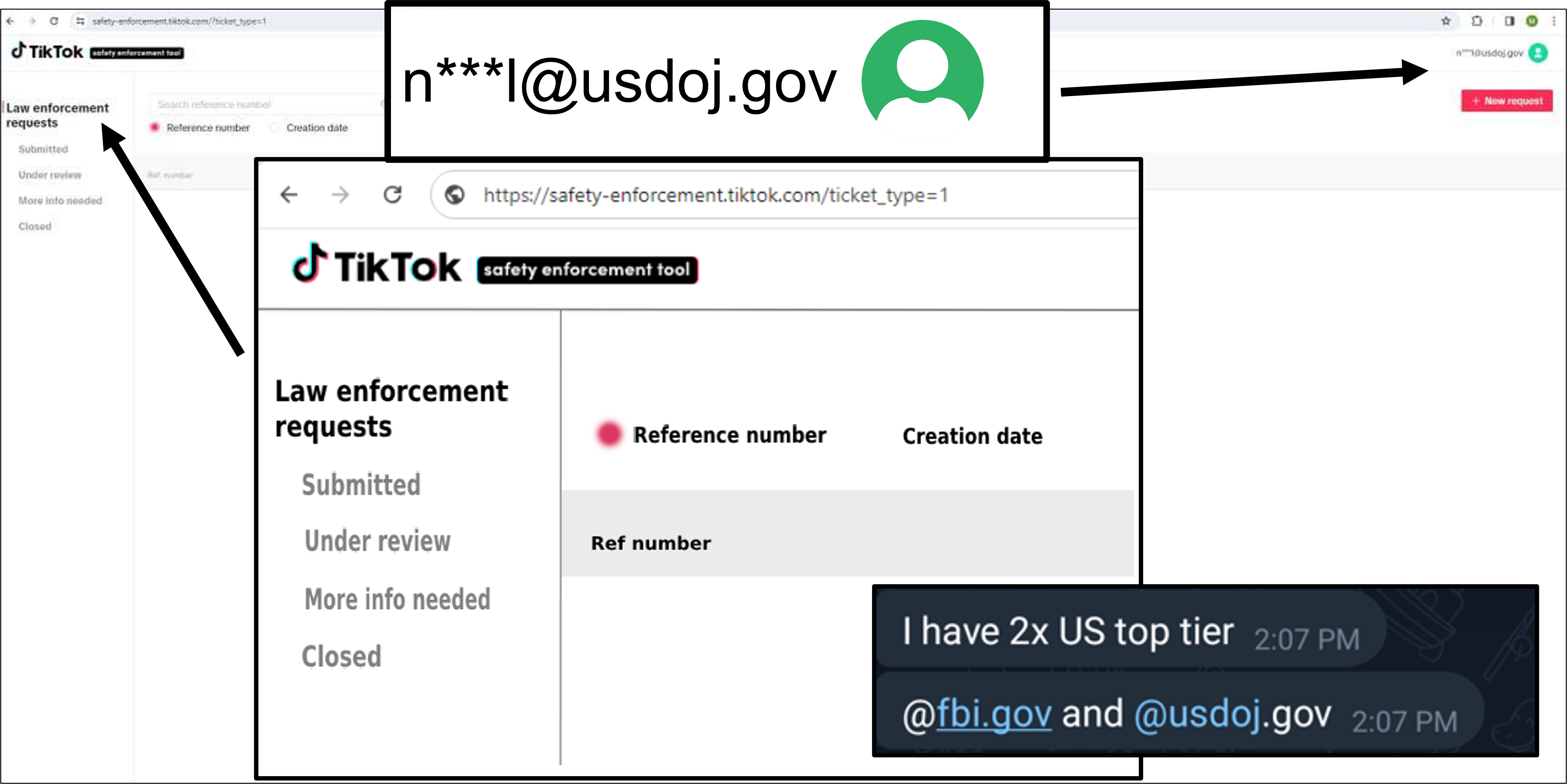

I also observed a threat actor who had multiple verified profiles on an Emergency Data Request aggregator. They were advertising services to submit fraudulent requests coming from USDOJ.GOV and FBI.GOV email addresses, boasting a high success rate.

They shared this screenshot of a USDOJ.GOV email address signed into a TikTok Law Enforcement Panel, ready to submit a fraudulent Emergency Data Request at a moments notice.

The following is evidence of other Law Enforcement Panels they claimed they could submit fraudulent Emergency Data Requests to.

Once the Emergency Data Request is completed, the adversary will try to use the information received, to compromise the victims personal accounts. This is done to get other sensitive information on the victim, to add to the dox and to extort them.

Historically, simply the fear of having personal information released was enough for victims to meet extortion demands. This was because adversaries had no way to intimidate their victims in real life, and it was seen just as a virtual threat. However, due to new ‘violence-as-a-service’ marketplaces, digital conflicts are now manifesting physically.

5. Violence-as-a-Service

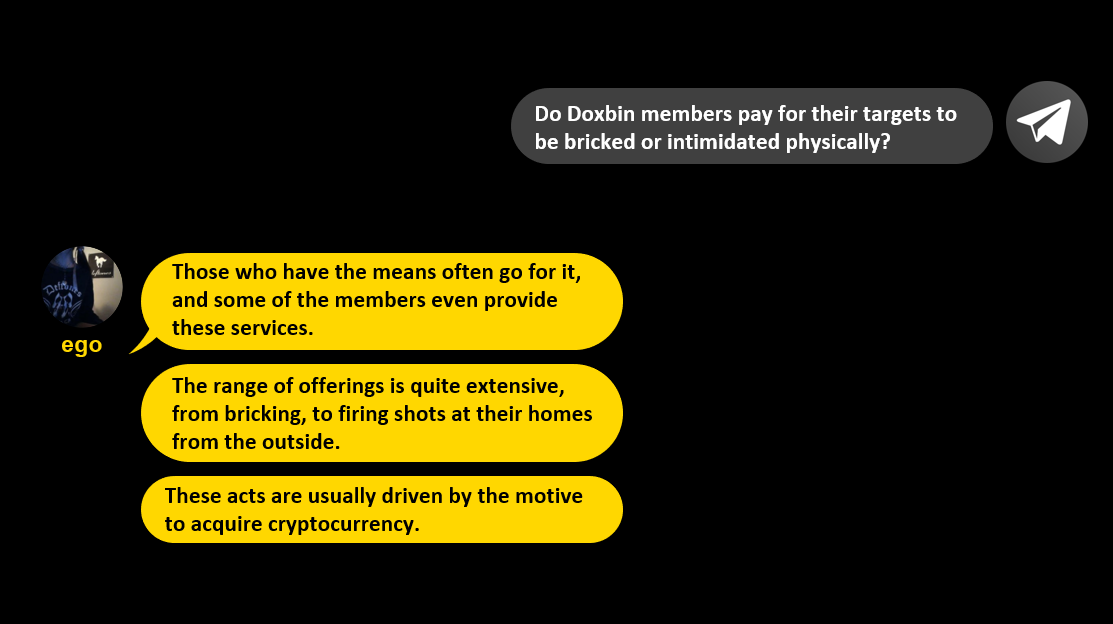

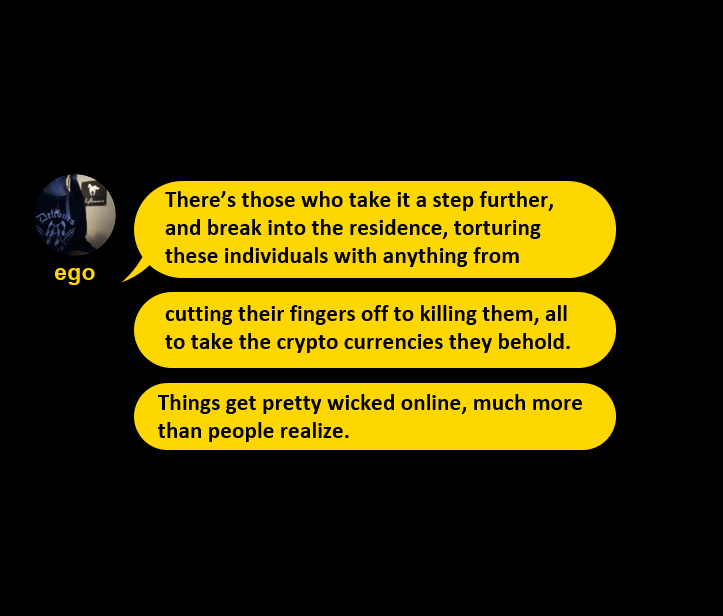

In my interview with “Ego”, I asked if Doxbin members pay for their targets to be intimidated physically. His response was “those who have the means often go for it, and some of the members even provide these services”. He also shared that, “the range of offerings is quite extensive, from bricking, to firing shots at their homes from the outside.” He explained that, “these acts are usually driven by the motive to acquire cryptocurrency.”

The following video is an example of physical intimidation services which ViLE has purchased, called a “house bricking”. Listen carefully to the audio to hear the adversary say “ViLE has come to get you! Bye bye”.

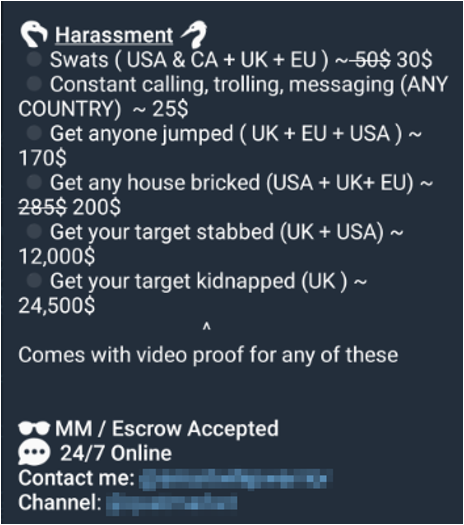

Services advertised in Telegram communities include swatting, getting jumped, house bricking, firebombing, stabbing and kidnapping. The following two videos are examples of services provided.

The first video is an example of a “shooting”, where an adversary will shoot a firearm outside a victim’s home.

The second video is an example of a “firebombing”, where an adversary will light a Molotov and attempt to throw it inside the victim’s home.

Purchasing the service of kidnapping may sound farfetched, but my interview with Ego shared more insights into the reality of these services.

He said that “things get pretty wicked online, much more than people realise”. This was because “there’s those who take it a step further, and break into the residence, torturing individuals, with anything from cutting off their fingers to killing them, all to take the cryptocurrencies they behold.”

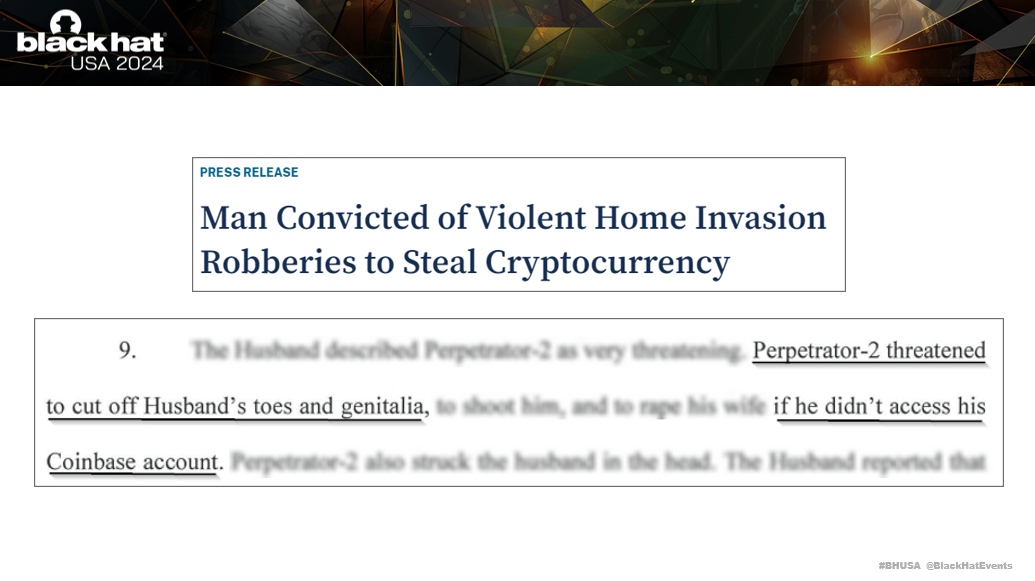

Cutting off fingers is quite different to throwing a brick through a window, however it is happening with recent arrests proving this.

In June 2024, a Florida man was convicted for doxing and extorting individuals for cryptocurrency. He would break into victims homes, take them hostage, and threat to cut off their fingers and toes. He wanted access to their cryptocurrency, just like Ego said what happens in the interview. This brings to life the types of doxing and extortion tactics used by doxing gangs like ViLE.

6. ‘Reiko’ and Doxing Legality

Within a couple months of “Weep” and “Convict” being charged by the Department of Homeland Security, ViLE disbanded. “Kt” the founder of Doxbin, also went into hiding and decided to part ways with Doxbin.

Doxbin was sold to an actor called “Operator” in June 2023, and “Reiko” stepped in as a new system administrator and developer.

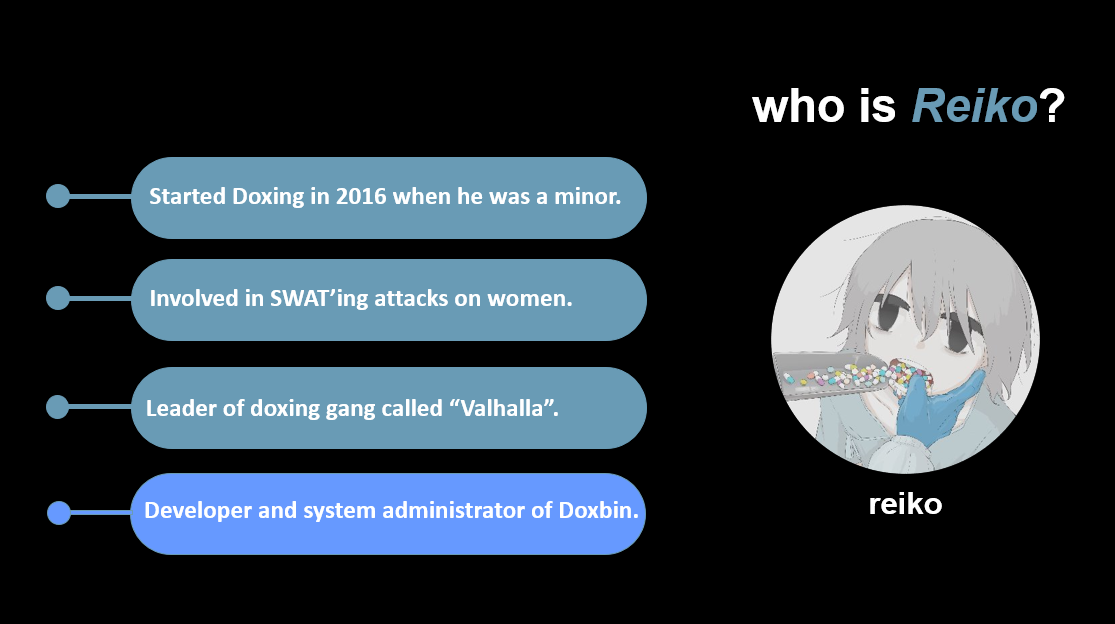

With an interest in wanting to better understand the legality of Doxbin, I was able to organise an interview with the new administrator “Reiko” to shed some light. The transcript of the interview is available here.

In the interview with Reiko, he shared that he started out in the doxing scene in 2016 when he was a minor. This indicates that he is in mid 20’s approximately.

He was also the member of a group involved in performing SWAT’ing attacks on young women. SWAT’ing involves phony 911 calls resulting in SWAT teams breaking into a victim’s home with the belief that a real threat is there. This is incredibly dangerous and is used as a physical intimidation tactic.

He later created a doxing gang called “Valhalla”, which the new owner of Doxbin “Operator” was a member of. He was wired by “Operator” to manage the ongoing development and system administration of Doxbin.

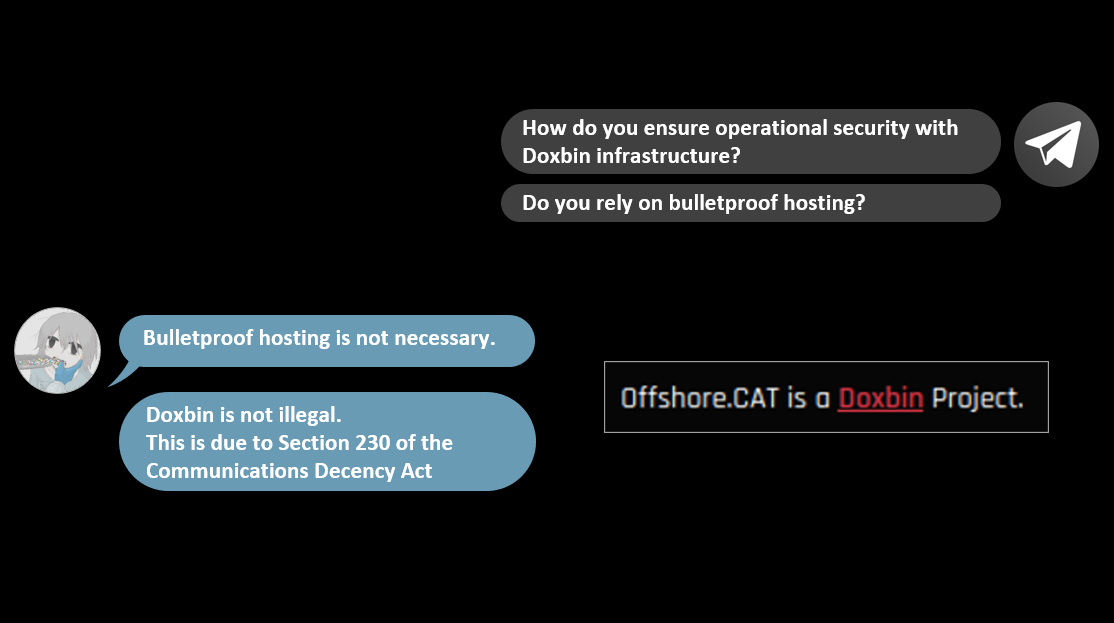

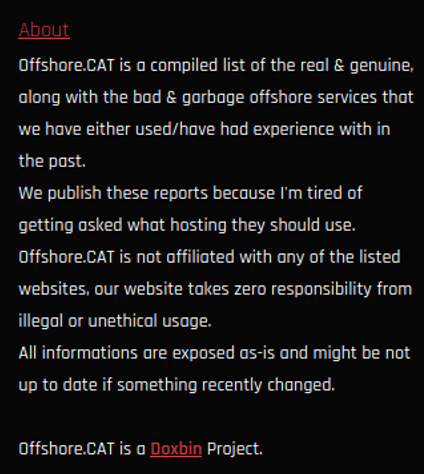

I asked Reiko about Doxbin’s operational security and if they relied on bulletproof hosting. His response was that “bulletproof hosting is not necessary”, as “Doxbin is not illegal”. However, this didn’t seem to be the case as upon further research I identified that Doxbin runs a service called offshore.cat.

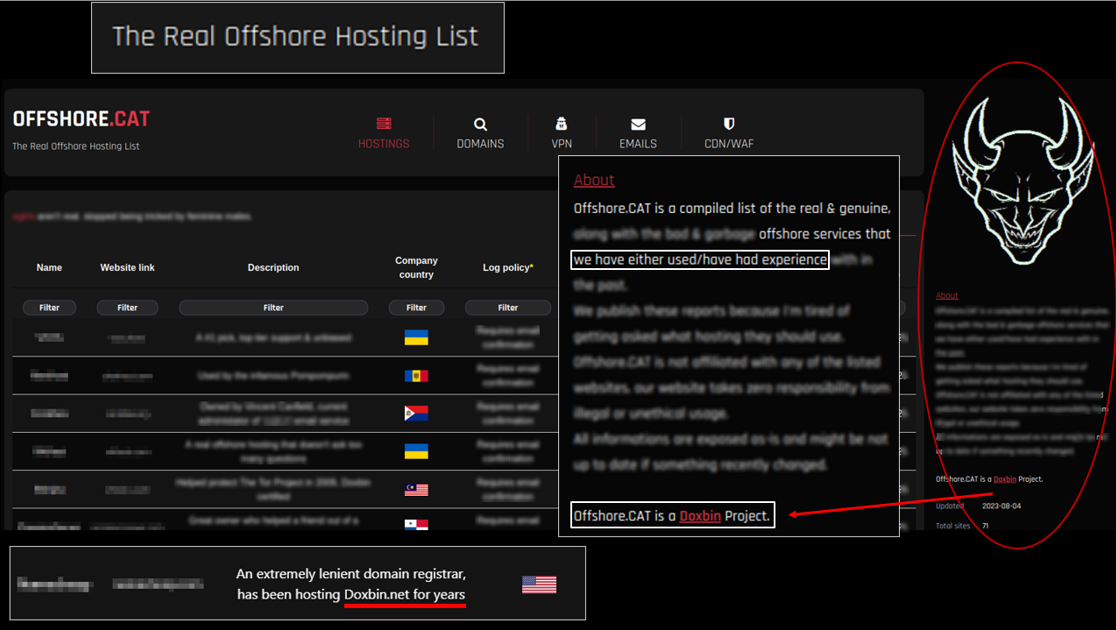

As per their website, offshore.cat recommends offshore hosting, and is also a Doxbin project. They recommend service providers that Doxbin has used, with 10+ reviews specifically mentioning Doxbin’s experiences. Filters include hosting providers which ignore DMCA requests, email providers with no logs, and domain registrars that ignore legal requests. It’s clear that offshore hosting providing is used because the site operates in a legal grey area.

Reiko also shared that the reason Doxbin is not illegal, is because of Section 230 in the Communications Decency Act (CDA).

The CDA is a US federal law which provides immunity to platforms that host or republish user’s content. This means, that Doxbin, and other websites which publish user’s content, cannot be held legally liable for what others say and do.

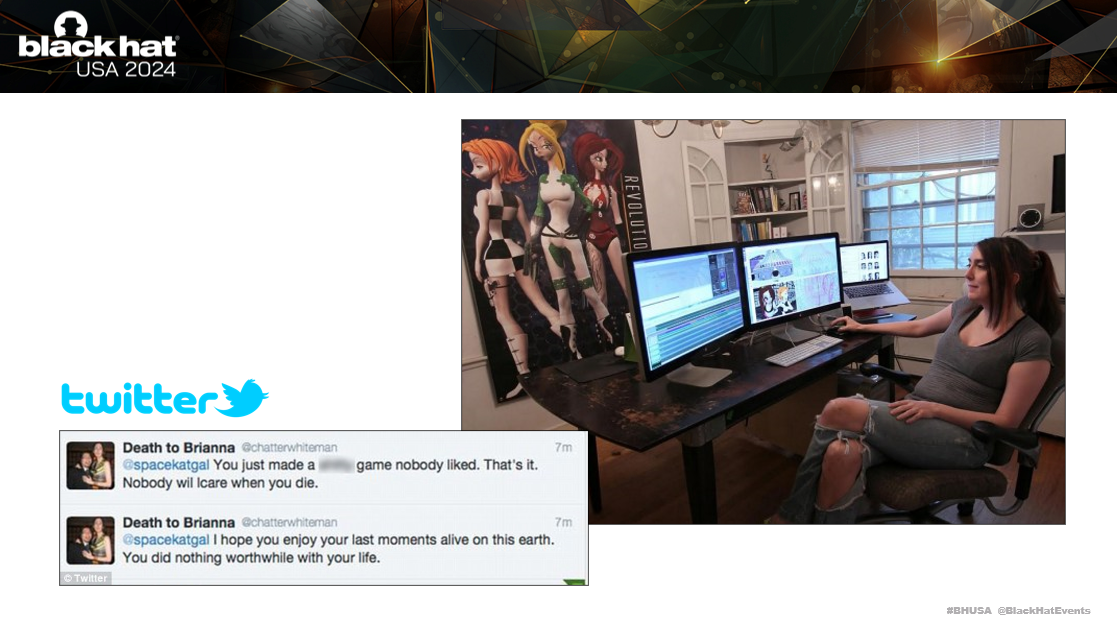

A case example of this is Gamergate. This was a case from a female game developer, Brianna Wu, against Twitter, after she received death threats in 2014. She sued Twitter, as Twitters users were sharing her dox on the platform. However, Twitter won the case, as they could not be held liable for what users uploaded to their website under the CDA.

Similar to this, Doxbin takes the stance that even though users may upload victims doxes which are used for harassment, they are not responsible or liable, due to the immunity provided by the CDA.

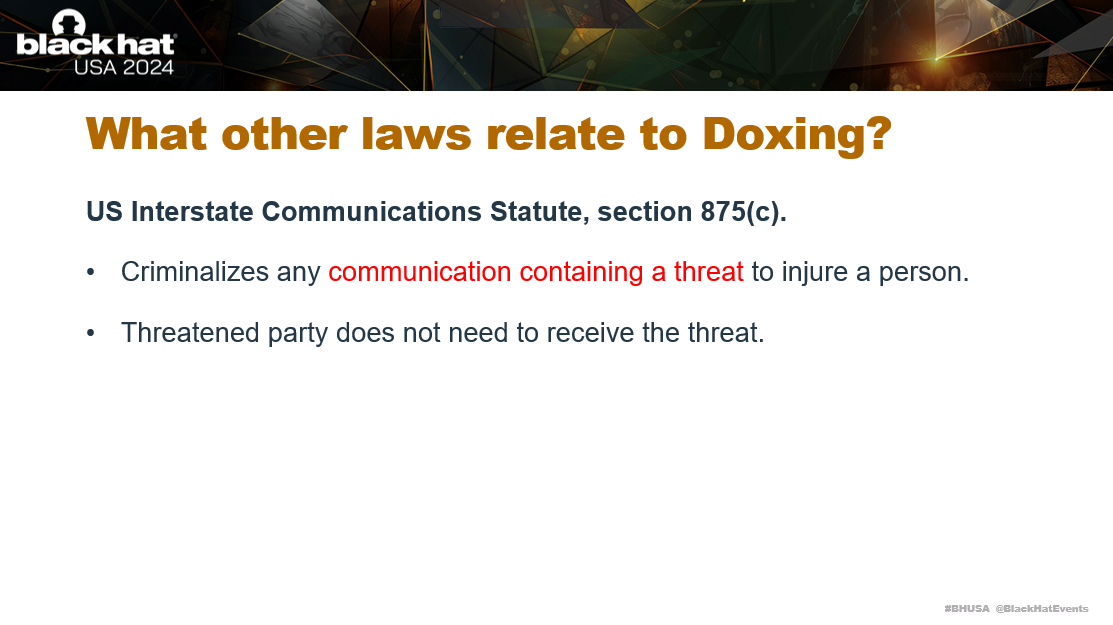

Now, there are other laws that broadly apply to Doxing and one of them is the US Interstate Communications Statute. This criminalizes any communication containing a threat to injure a person. The important part is containing a threat, and under the law, the threatened party does not need to receive the threat.

So for example, if a person’s dox was published on Doxbin that included a threat, even if the user doesn’t receive the threat directly, this will violate the US Interstate Communications Statute.

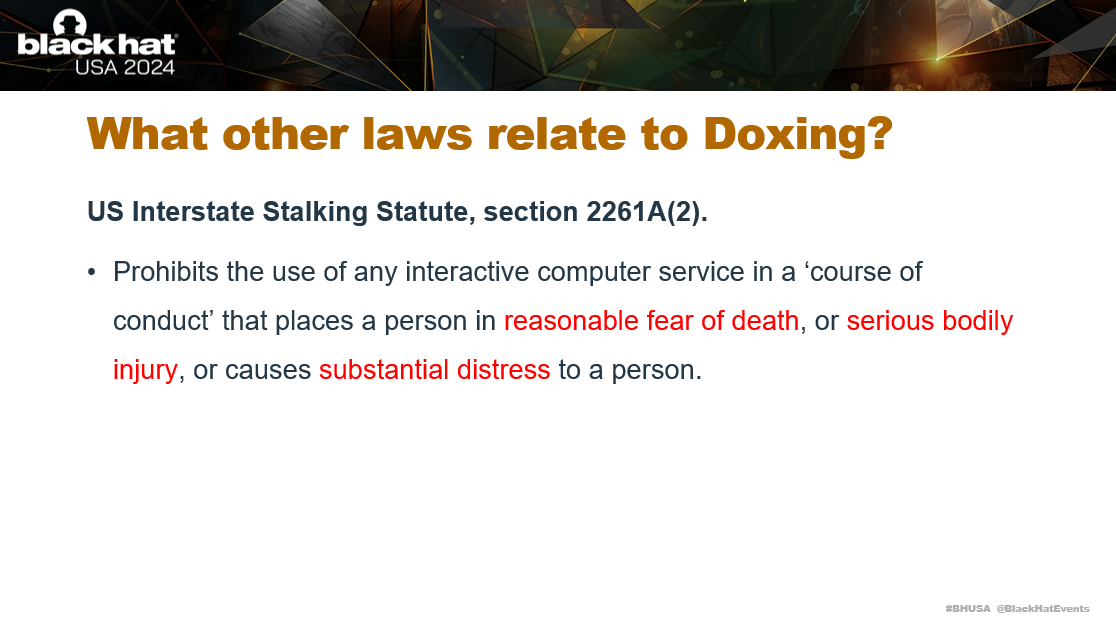

There is a third piece of legislation that applies to doxing, which is the US Interstate Stalking Statute. This prohibits any use of interactive computer services that places a person in reasonable fear of death, serious bodily injury, or causes substantial distress. There is no case law related to a published dox causing a person to feel these impacts, but it is easily proven if the published Dox does contain a threat.

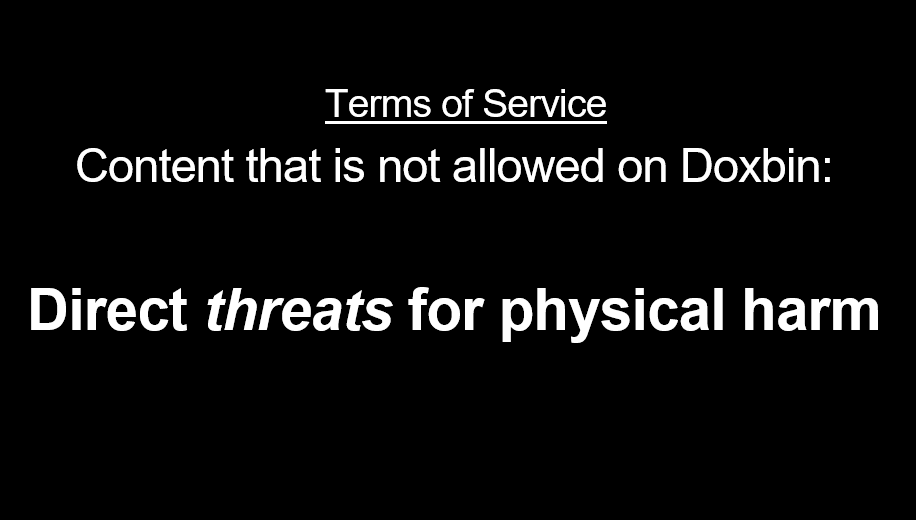

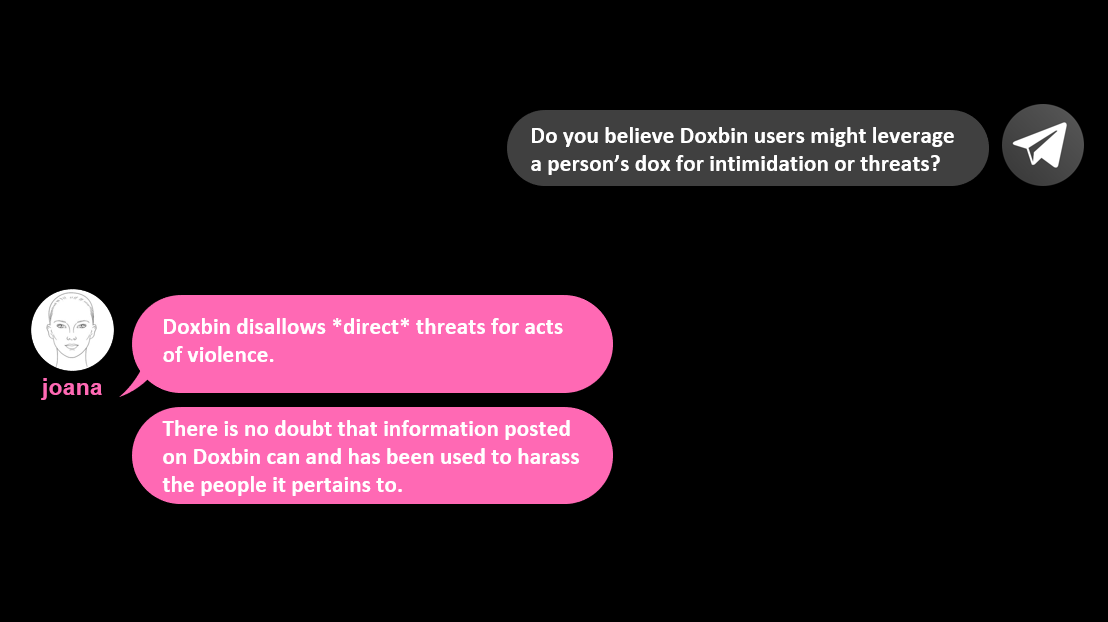

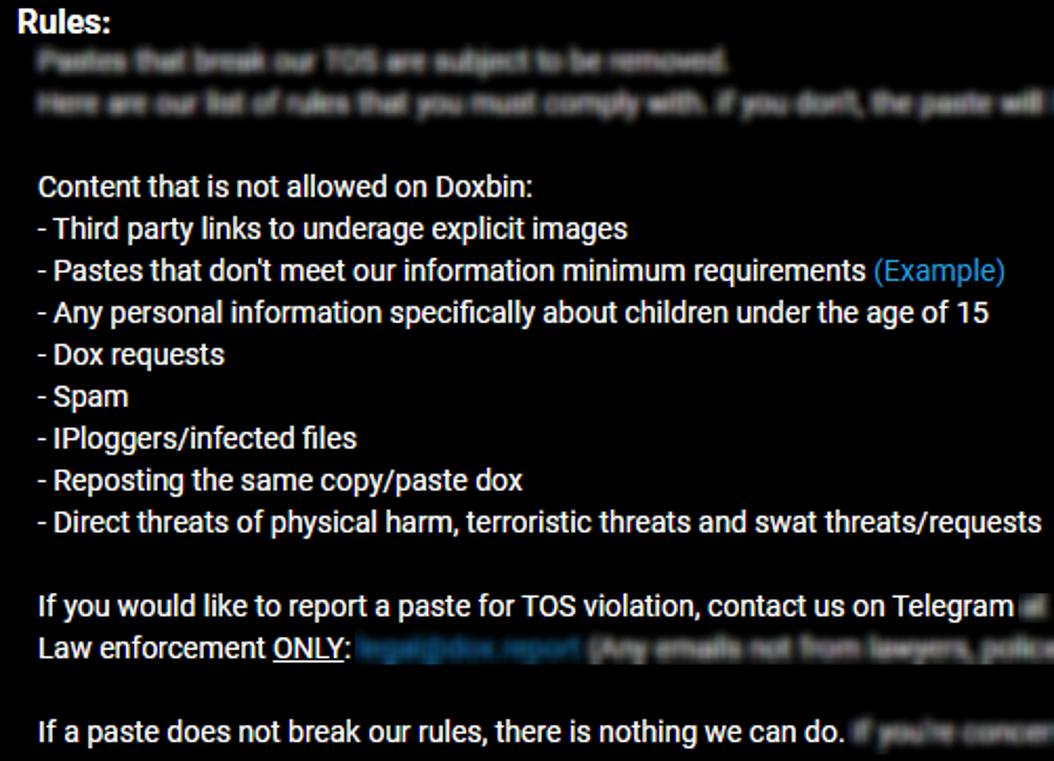

I shared earlier in the presentation that Doxbin prides themselves on being a platform where doxes are not taken down, except if it breaks their terms of service. Doxbin, aware of these laws, has created their terms of service to circumvent legal liability. This has been done by disallowing doxes to include direct threats of physical harm. This makes it difficult for law enforcement to prove that a Dox violates US Interstate Stalking or Communications Statutes. Whilst direct threats are not allowed, an interview with another Doxbin member provided more insights.

I spoke to “Joana” a prolific member of Doxbin with over 2000 posted doxes. They shared that whilst Doxbin disallows direct threats for acts of violence, there is no doubt that information posted on Doxbin is used for acts of violence. Sharing a victims dox could have the intention of intimidation, but if it doesn’t include a direct threat, it complies with all US laws. This creates an ambiguous stance, as there is nothing remaining under US law that prohibits Doxbin from running.

As mentioned earlier, Doxbin will take down a dox if it violates their terms of service. Other types of content that is not allowed includes link to underage explicit images, personal information on children, and anything else obtained illegally. However, Doxbin doesn’t proactively review any published content to see if it complies with their terms of service.

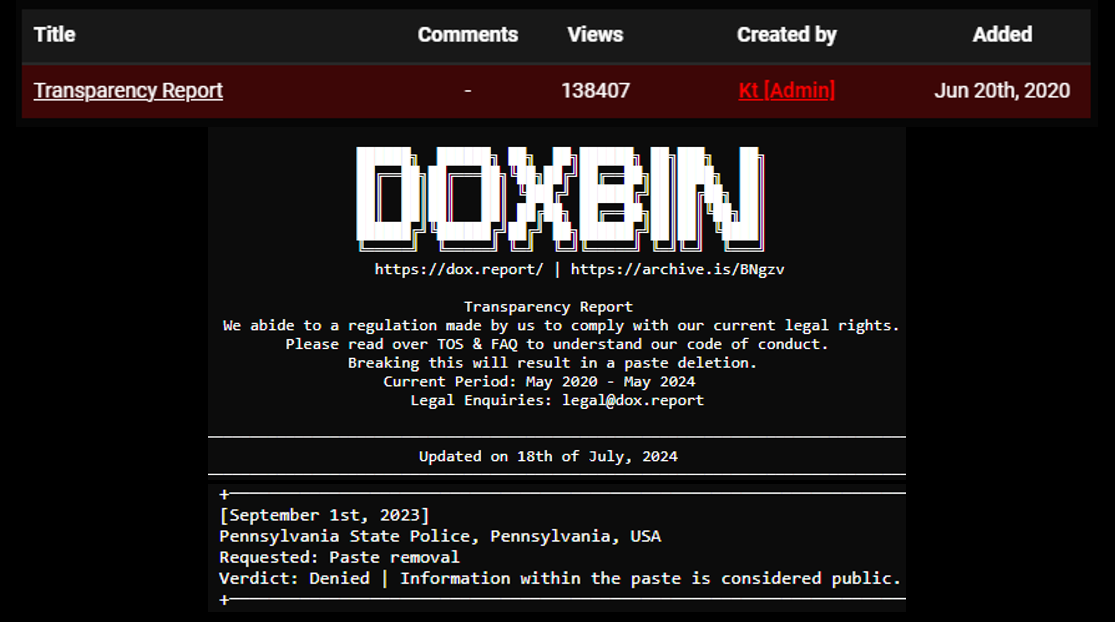

Instead, they have a public record called the “Doxbin Transparency Report”, which includes a list of government agency requests to take down information. They record the government agency name, the request, and the decision made. For example on the slide below there is a request from Pennsylvania State Police in the USA.

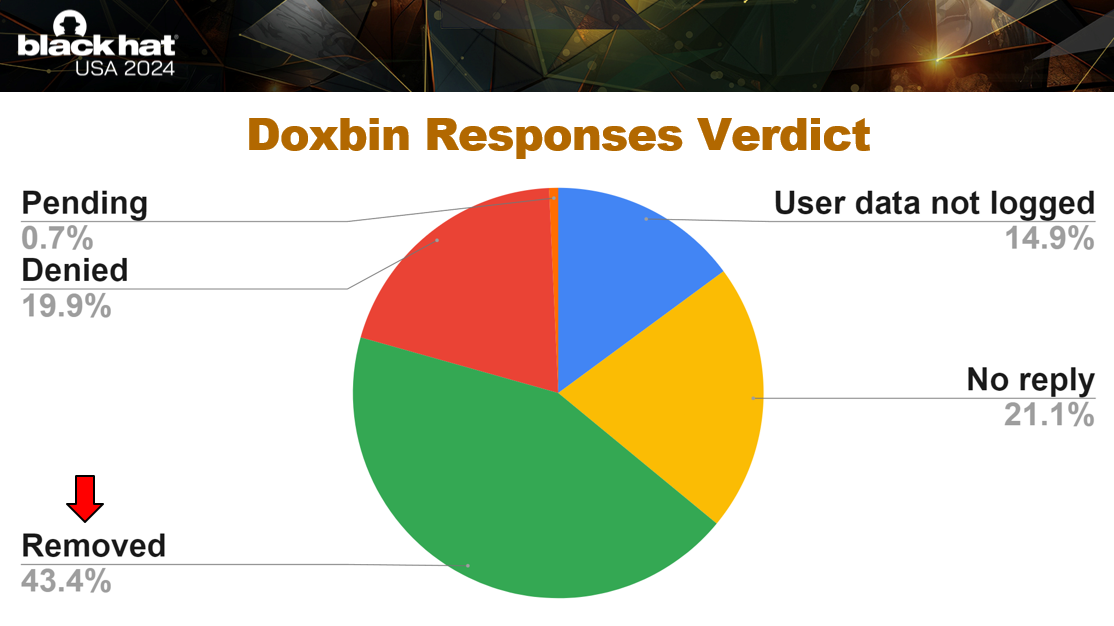

Doxbin has received 141 government agency requests from 27 different countries. Only 43% of these requests resulted in a dox being removed. This means only 60 out of a possible 165,000 doxes have been taken down from the site.

It’s clear that Doxbin uses the transparency report to masquerade as complying with government requests and running a legitimate website. However, they are actually operating in a legal grey area, due to gaps in US Policy.

They’ve carefully constructed their terms of service to exploit these gaps and avoid legal liability.

7. Recommendations

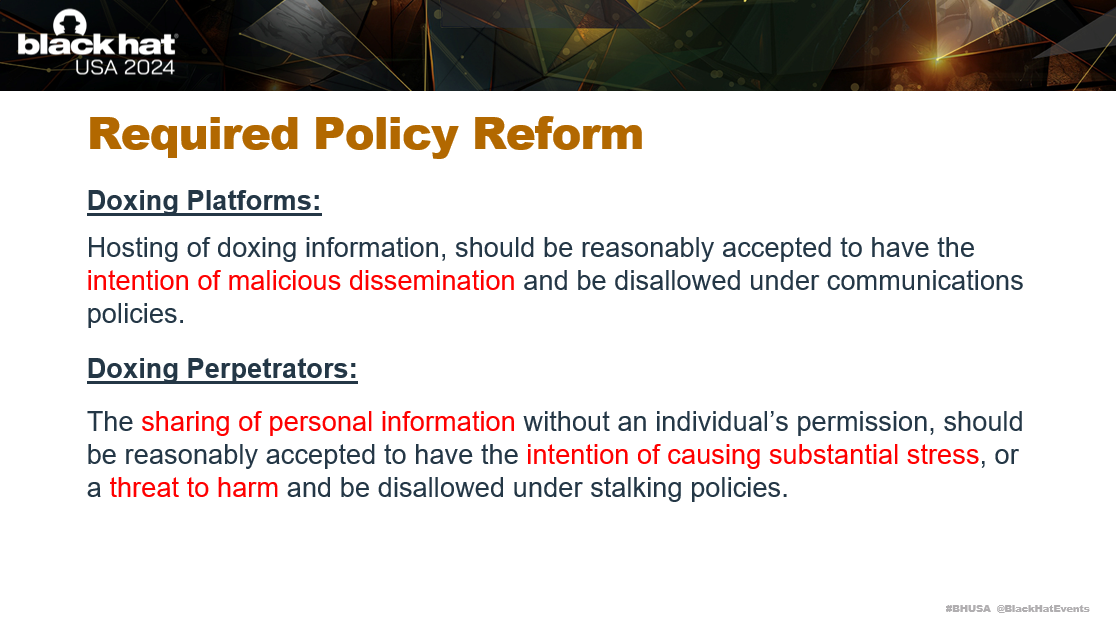

Due to these gaps, policy change is required to better protect victims. Communications laws should be updated to include that the hosting of personal information has the intention of malicious dissemination. Stalking laws should be updated that the sharing of personal information without permission, has the intention of causing harm and stress.

Whilst I have been a victim of doxing myself in the past, I recognised that there was a new level of risk associated with conducting this research. I made some changes to protect my privacy and personal safety, that I would like to share with you as takeaway advice. But first it’s important we cover the basics.

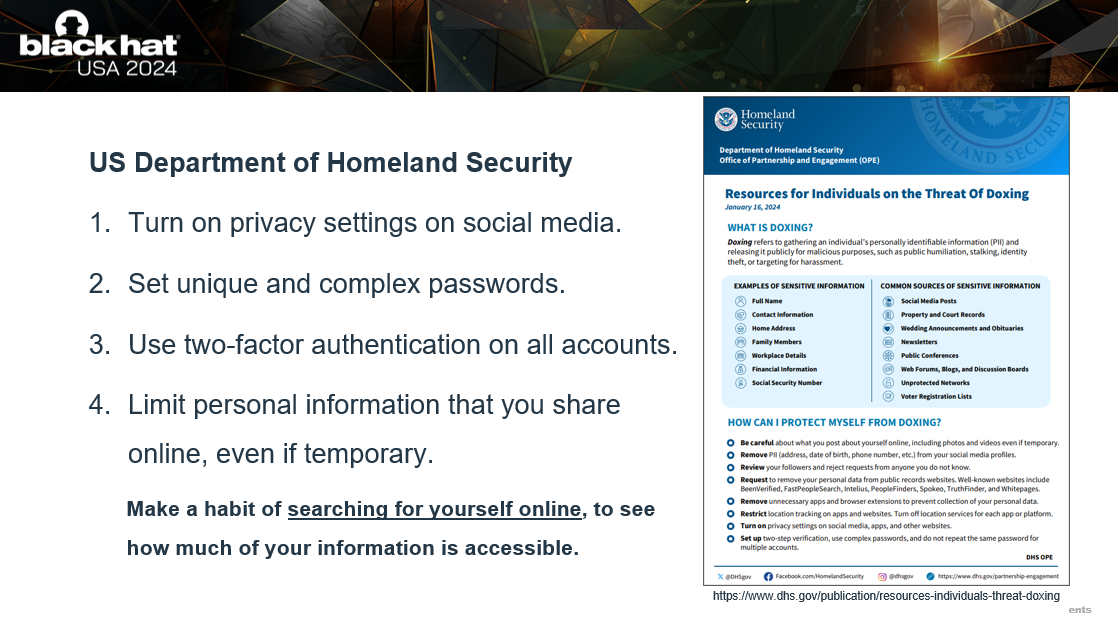

The US Department of Homeland Security has shared some comprehensive advice on how you can protect yourself from doxing.

- Make sure you remove all personally identifiable information from your social media profiles and enable the highest privacy settings.

- Set unique and complex passwords, I use a password manager to make this easier.

- Enable two-factor authentication on all accounts, and I recommend you use Google Authenticator rather than an SMS-based verification (I will explain why in more detail later).

- Limit the personal information you share, and I recommend making a habit of searching for yourself online. You will be able to see how much information is accessible, and if you can get it taken down.

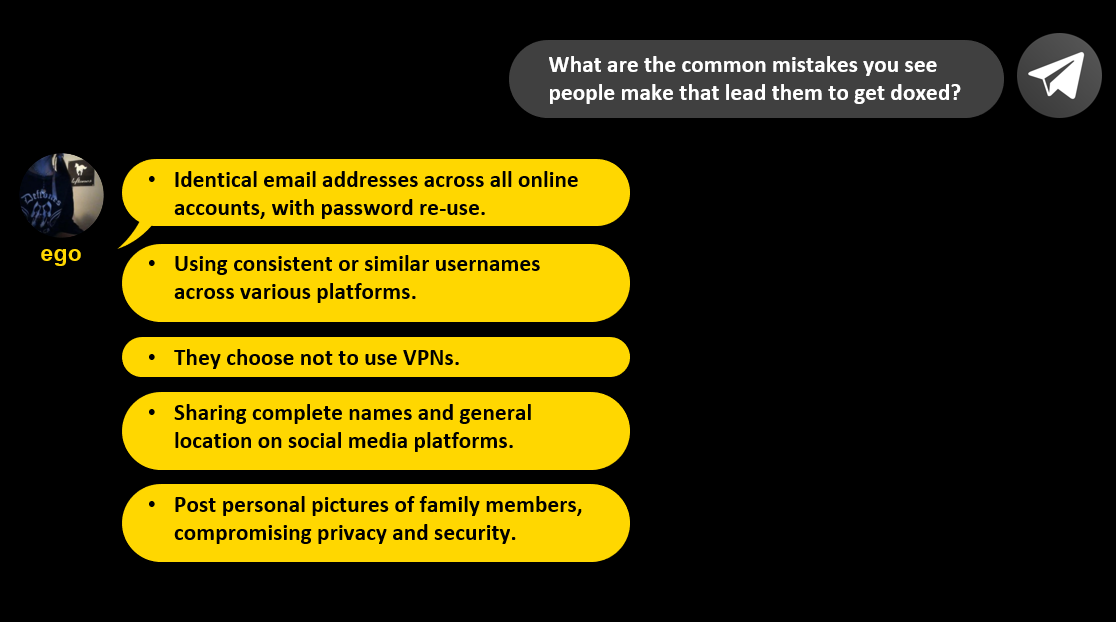

I also asked Ego what are the most common mistakes that lead to people getting doxed.

He shared using identical usernames and passwords across websites and oversharing personal information, including posting pictures of family members. If you follow the advice I shared earlier, you will be able to mitigate these common mistakes. There are also other steps you can take, to protect yourself from more sophisticated doxing techniques.

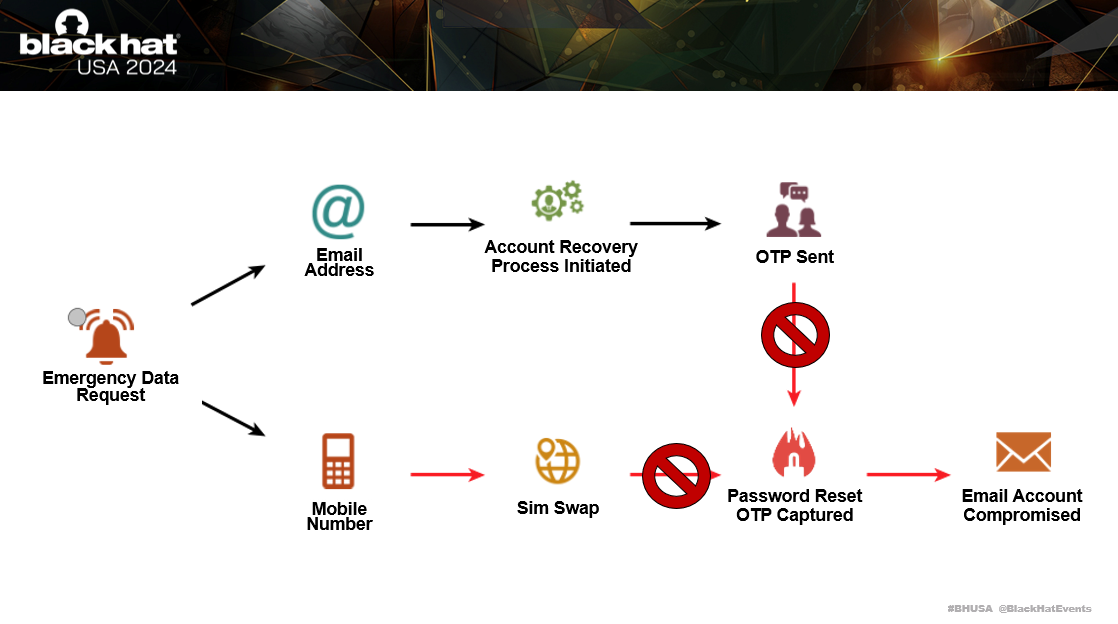

Earlier on I shared this diagram of what happens when a fraudulent Emergency Data Request is completed. One of the objectives of the adversary is to hijack your primary email account.

There isn’t anything that you can do to disrupt the success rate of a fraudulent Emergency Data Request, as that requires industry changes. However, you can disrupt the attack chain which is used to compromise your email account.

It’s better to assume that a fraudulent Emergency Data Request has already been completed on you and take steps to mitigate further compromise.

When the Emergency Data Request is completed, the adversary will get your email address and mobile number. They compromise your account through the forgot password account recovery process.

This is where a One-Time Pass (OTP) code is sent to your mobile number, to reset access to your account. They perform a sim swap attack, to port forward your mobile number to a new sim card they control. This allows them to receive the OTP code and change the password to your account.

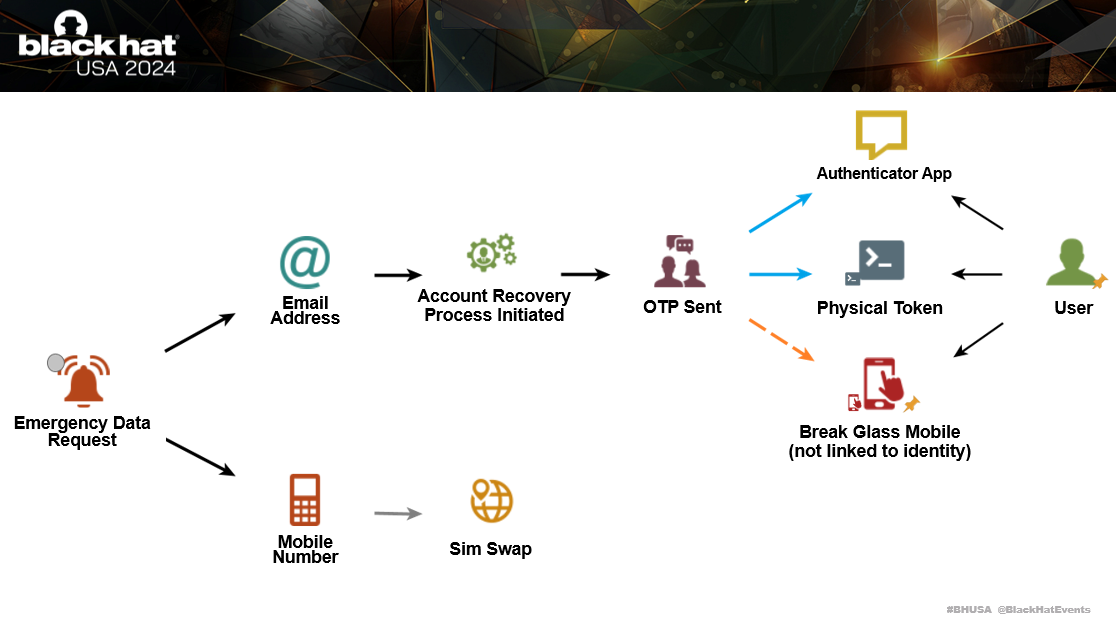

To disrupt this attack chain, we need to make sure the adversary can’t get the OTP code.

This is achieved by removing SMS as a multi-factor authentication option on all of your accounts. This means, that even if they sim swap your mobile number, they won’t be able to hack your accounts.

Your multi-factor authentication must always be with either an Authenticator-based app, or a physical token.

Only in exceptional circumstances should you have a break glass mobile number for SMS-based authentication. But it cannot be linked to your identity, otherwise it can be easily discoverable by an adversary using malicious insiders at mobile carriers.

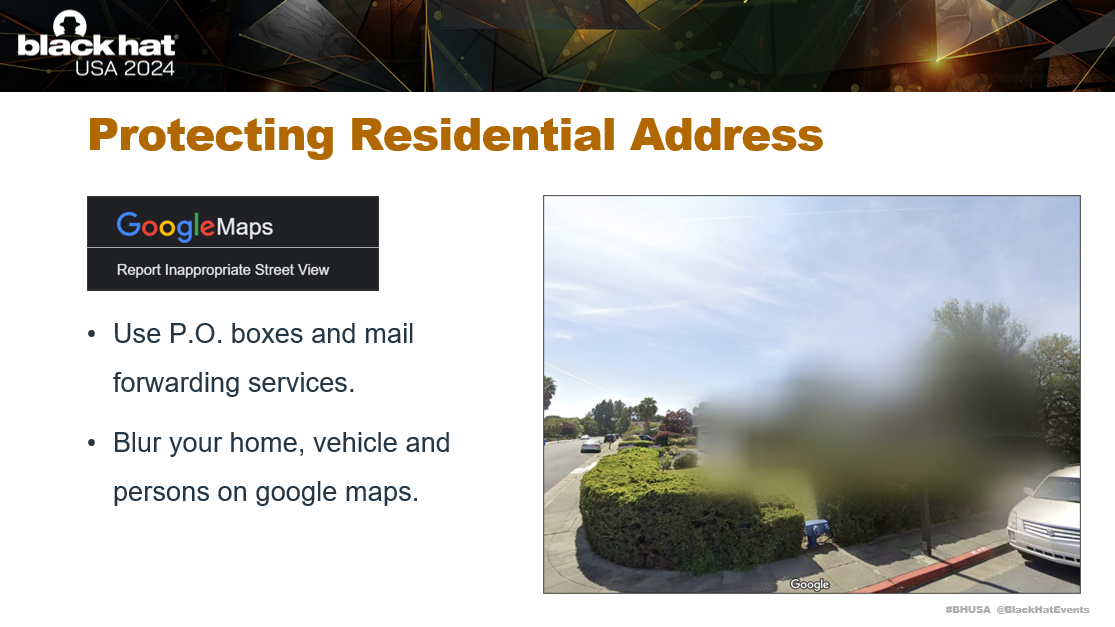

Now to improve your personal safety, you need to protect your residential address. You could use use P.O. boxes and mail forwarding services for your deliveries. However, it is likely your address is already included somewhere in your digital footprint online, and it’s not cheap or easy to change your address.

To hinder reconnaissance of your home by attackers, you can request to have your home blurred on Google Maps. This can be done using the ‘Report Inappropriate Street View’ functionality.

If you are a researcher or hold cryptocurrency, you may also want to make additional changes to protect your personal safety. I have installed CCTV, floodlights and intrusions alarms at my personal property. Depending on where you live, you could also acquire a licensed firearm for self-defence. I have a baseball bat under my bed which is helpful too.

8. Conclusion

We’ve covered a lot today. To conclude, remember these crucial points:

- Doxing is no longer just a virtual threat; it has evolved into a tool used for real world extortion.

- Limit the personal information you share online and make the habit of trying to dox yourself.

- Never secure your accounts with SMS-based authentication.

- Blur your home on Google Maps and implement physical deterrents.

9. Credit

- Credit to Zach Stanford (@svch0st) for a massive help in the initial research phase, assisting with the preparation of interview questions, and connecting me with relevant industry professionals.

- Credit to Shanna Daly (@fancy_4n6) and Lidia Giuliano (@pink_tangent) for their mentorship in the Black Hat Speaker’s Program.

- Credit to Chis Rock (@chrisrockhacker) for providing feedback on my CFP submission.

- Credit to Angus Strom (@0x10F2C_) for providing feedback on my CFP submission.

- Credit to Bex Nitret (@4n6Bexaminer) for inspiring me to complete investigative-style security research.

10. References

- Doxbin

- ViLE

- Offshore.cat

- WIRED - What is Doxing

- DailyDot - Silk Road trial judge may have been doxed and threatened

- Vice - What Happens When a Lawyer Takes on a Hacker

- KrebsOnSecurity - Two USA Men Charged in 2022 Hacking of DEA Portal

- US Department of Justice - Two Men Charged for Breaching Federal Law Enforcement Database and Posing as Police Officers to Defraud Social Media Companies

- US Department of Justice - Two Men Plead Guilty to Computer Intrusion and Aggravated Identity Theft for Hacking into Federal Law Enforcement Web Portal

- NYDailyNews - Members of ViLe online group charged by Brooklyn feds with using stolen police credentials for doxing scheme

- Vice - Nobody is Safe in Wild Hacking Spree

- BBC - LAPSUS$ Oxford teen accused of being multi-millionaire cybercriminal

- BBC - LAPSUS$: GTA 6 Hacker Handed Indefinite Hospital Order

- KrebsOnSecurity - NJ Man Hired Online to Firebomb, Shoot at Homes Gets 13 Years in Prison

- KrebsOnSecurity - Violence-as-a-Service, Brickings, Firebombings and Shootings for Hire

- CourtListener - United States vs McGovern-Allen

- YouTube: Ironic - The Dark History of Doxbin

- KrebsOnSecurity - Hackers Gain Power of Subpoena via Fake ‘Emergency Data Requests’

- US Department of Justice - Man Convicted of Violent Home Invasion Robberies to Steal Cryptocurrency

- WIRED - Inside a Violent Gang’s Ruthless Crypto-Stealing Home Invasion Spree

- CourtListener - United States vs Seemungal

- US National Institute of Justice - Ranking Needs for Fighting Digital Abuse

- Witwer, A. R., Langton, L., Vermeer, M. J., Banks, D., Woods, D., & Jackson, B. A. (2020). Countering technology-facilitated abuse: Criminal Justice Strategies for combating nonconsensual pornography, sextortion, doxing, and swatting. RAND

- Australian Government eSafety Commissioner - Doxing Tech Trends and Challenges

- US Department of Homeland Security - Resources for Individuals on the Threat of Doxing

- Electronic Frontier Foundation - Section 230 Communications Decency Act

- HudsonRock - Infostealer Infections Lead to Hacking of Google, TikTok, and Meta Law Enforcement Systems

- Michigan Technology Law Review - Online Harassment and Doxing on Social Media

- Batuhan Kukul, Personal Data and Personal Safety: Re-examining the limits of public data in the context of doxing, International Data Privacy Law, Volume 13, Issue 3, August 2023, Pages 182-193

- Julia M. MacAllister, The Doxing Dilemma: Seeking a Remedy for the Malicious Publication of Personal Information, Fordham Law Review, Article 44, 2017

- Schuster, J., Franz, A., & Benlian, A (2024). What Makes Doxing Good or Bad? Exploring Bystanders’ Appraisal and Responses to the Malicious Disclosure of Personal Information

- Shan, G., Pu, W., Thatcher, J. B., & Roth, P. (2024). How Doxing on Social Media Leads to Social Stigma and Perceived Dignity.